The NZCat Team has a vision for a secure New Zealand, resilient to large scale global disruptions and catastrophic risks. We’ve been researching anticipatory governance of risk, the process of effective national risk assessment, and we’ve published peer-reviewed research on specific risks such as pandemics, nuclear war, massive volcanic eruption, and risks from artificial intelligence.

Most recently we developed a NZ Hazard Profile for nuclear war, and conducted a cross-sector survey of this hazard, its likely impacts and mitigation strategies. We are now undertaking an in-depth interview study to consolidate this information before we publish our global catastrophes policy agenda in late 2023.

This background meant that we were very interested when the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet called for submissions on their “Strengthening the resilience of Aotearoa New Zealand’s critical infrastructure system” Discussion Document.

The Discussion Document asks whether and how NZ’s critical infrastructure systems ought to be regulated to ensure resilience in the face of hazards, threats, and megatrends.

We have now made a detailed submission on this document noting that regulation is only one aspect of the systematic development of resilience, and arguing the need for better definitions, a wider net, a more systematic approach to national risk, and more focus on potential global catastrophes.

We encourage anyone else who thinks New Zealand needs to improve resilience to hazards and threats, across sectors such as food, energy, transport, and communications to make your own submission here.

You can read our full submission.

Or you can read the Executive Summary of our submission as follows…

Submission to the New Zealand Government: Strengthening the resilience of Aotearoa New Zealand’s critical infrastructure system

Executive Summary

We applaud the initiative to enhance the resilience of New Zealand’s critical infrastructure. In response to the Discussion Document, we make the following key points (explained in more detail in the full submission below).

- A distinction needs to be made between ensuring existing critical infrastructure is resilient and investing in infrastructure needed for resilience. NZ needs more of the latter (we give examples below) and this should be legislated.

- A further distinction needs to be made between infrastructure needed for survival (eg water, agriculture, food transport, heating, etc) and merely critical infrastructure. The current Emergency Management Bill does not yet achieve this.

- Regulation of survival and critical infrastructures should not stop at requirements for currently existing infrastructure. There are resilience infrastructures NZ currently lacks that would be critical to survival in certain catastrophe situations (eg, domestic biofuel production capacity, coastal shipping, seed stockpiles, etc). New Zealand must foster ‘resilient’ infrastructure and develop ‘resilience’ infrastructure.

- Any regulatory approach to critical national infrastructure needs to be informed by a properly resourced, systematic, public, and transparent National Risk Assessment that addresses all hazards and all threats to help prioritise risk mitigation activity.

- All hazards and all threats must mean exactly that (not just familiar or recent hazards such as flooding, earthquakes, or Covid-19) and explicitly include the global catastrophic risks that likely contain most of the risk to NZ. The risks should include catastrophic trade isolation and its impact on critical infrastructure.

- New Zealand could replicate something like the US Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act 2022 that defines and lists such risks and defines ‘basic needs’.

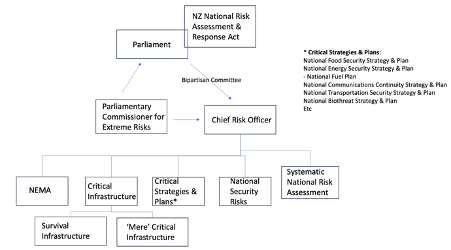

- If not the above detailed US-style legislation, there could be a NZ National Risk Assessment and Response Act, requiring government to conduct a regular comprehensive, publicly facing, systematic assessment of national risks, including cross-border global catastrophic risks, and to engage with the public, experts, and other stakeholders, including Australia, on these risks and possible solutions.

- The National Risk Assessment could be coordinated by a Chief Risk Officer or Parliamentary Commissioner for Extreme Risks tasked with overseeing and advising on the systematic national approach to risk, including regulation (see Figure above).

- There should be a public discussion, including government, media, and crowdsourcing of possible solutions, that explicitly addresses the trade-off between standard of living and security in the face of catastrophic risk, with clear options on the table for addressing resilience, and funding these investments.

- People today and in the future deserve equitable protection from risks, so investment in resilience should occur immediately, financed by borrowing, and paid for across the lifetime of the resilient infrastructure by all of those who benefit.

- The distinction made between ‘survival infrastructure’ and ‘merely critical infrastructure’, should leave government responsible for investing in, and maintaining survival infrastructure where it is not economic for the market to do so.

- Any ‘minimum standards’ should be informed by analysis of second (and higher) order impacts, for example using a NZ digital twin for plausible risks and using downward counterfactual analysis of previous events.

- We need to better understand the risks before contemplating minimum standards in the face of those risk conditions. However, minimum standards should include mandatory cooperation among providers/sectors/government and pre-catastrophe simulation/scenario exercises.

- The Government should be transparently clear with the public about the overarching framework for systematically approaching national risk, and employ a legislative and governance structure that does not omit key risks (ie includes clear responsibilities for addressing such risks as Northern Hemisphere nuclear war, bioweapon pandemic, climate altering volcanic eruption, severe solar storm, and other similar risks, all of which originate overseas, and none of which is a ‘malicious threat to NZ’).

You can read our full submission here.