Matt Boyd, Sam Ragnarsson, Simon Terry, Ben Payne, Nick Wilson

TLDR/Summary

- In the wake of a global catastrophe that severely disrupted liquid fuel trade, New Zealand would face significant challenges in sustaining food production.

- The nation consumes over 3.7 billion litres of diesel annually but has only 21-days’ supply onshore at any time. Even with rationing, agriculture would struggle to maintain food production in an extended fuel supply crisis.

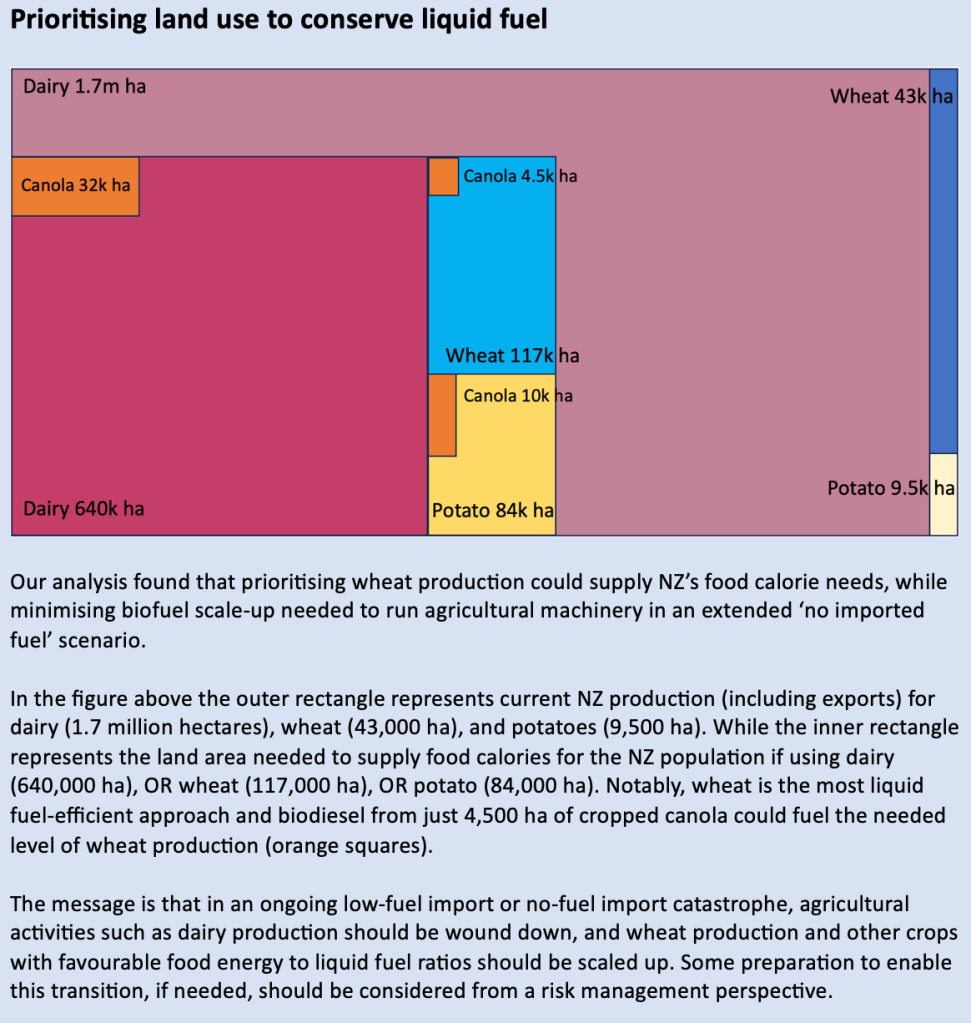

- Pivoting to crops with higher per-hectare food energy yields, like wheat or potatoes, could be more fuel-efficient and help NZ survive a catastrophe. Wheat’s frost resistance could be beneficial in a volcanic or nuclear winter.

- Our new analysis (paywalled, preprint available here) published in the international journal Risk Analysis, shows that local biofuel production of 5 million litres a year could sustain the minimum food production required to feed the population if resources are strategically deployed in anticipation.

- One feasible feedstock for biodiesel, canola, is already grown and has previously been refined for biodiesel in NZ.

- Recent discussions and studies emphasise the need for a comprehensive fuel and food security plan in New Zealand.

Introduction

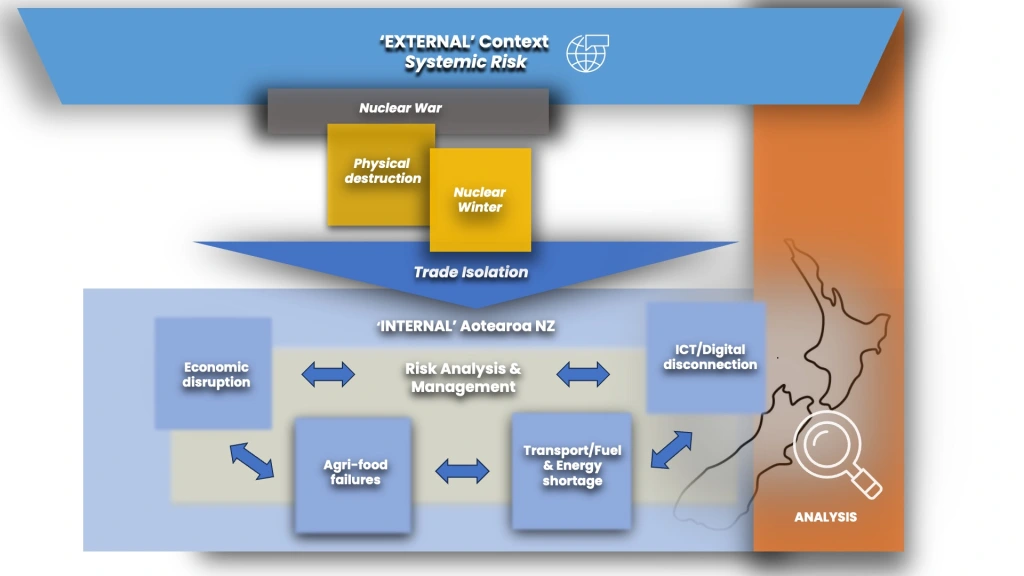

A global catastrophe would likely disrupt trade in liquid fuels. A severe catastrophe such as a nuclear war could disrupt supplies for many years or indefinitely. Countries dependent on imported oil products might struggle to sustain industrial agriculture due to their reliance on diesel. Island nations importing 100% of refined fuels, where stored diesel would be quickly exhausted, are particularly vulnerable.

Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) consumes over 3.7 billion litres of diesel per year, with onshore stored holdings of approximately 213 million litres, just 21 day’s supply. Agriculture consumes 295 million litres (before including agriculture-related road transport). With other competing essential demands on diesel, rationing alone will not allow current reserves to sustain food production through a lengthy catastrophe.

New Zealand may find that continuing production of dairy products that would ordinarily be exported may not be optimal in a global catastrophe where shipping of milk solids is not possible and dairy production consumes a lot of liquid fuel.

Increasing production of very high per-hectare (ha) food energy crops such as wheat or potatoes, would allow more efficient use of limited liquid fuel. Additionally, wheat is frost resistant, which might help in any volcanic or nuclear winter scenario.

One possible strategy is to attain a minimum level of fuel self-sufficiency through the sustainable local production and refining of biofuels, including biodiesel and renewable diesel.

In a new paper, just published in the international peer-reviewed journal Risk Analysis, we analyse the merits of expanding canola production as a biodiesel feedstock, coupled with a pivot to more efficient crops. We deduce the minimum land and liquid fuel requirements to sustain minimum industrial agriculture and feed the NZ population.

Key Findings

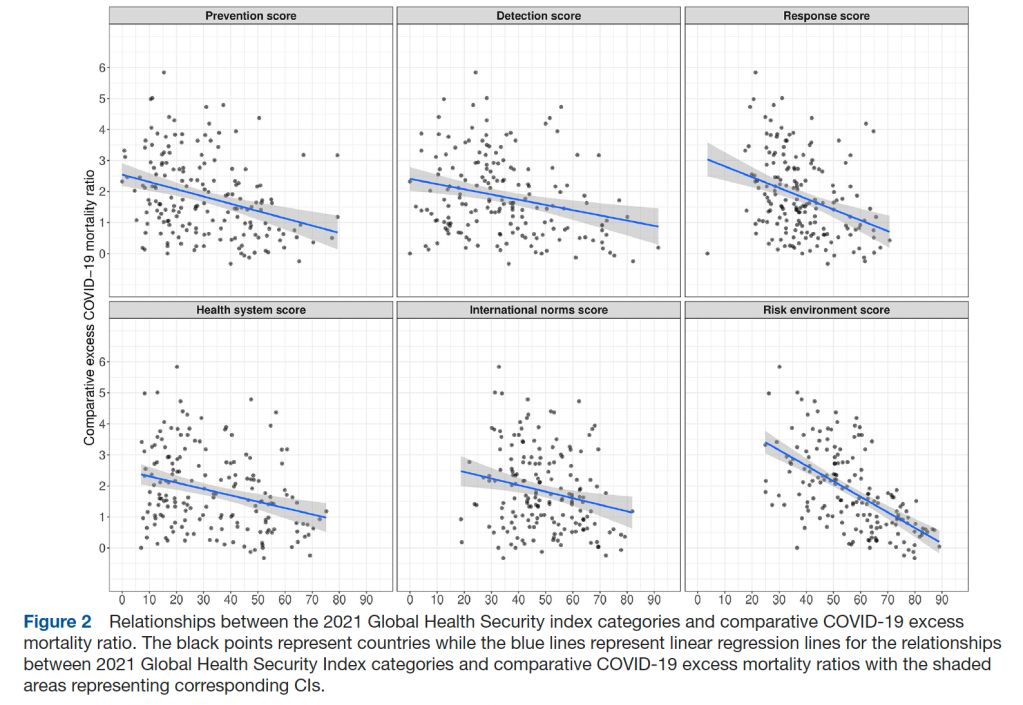

Farming a smaller land area would require less liquid fuel. Therefore, we identified crops with high food calories per unit of land (wheat, potatoes) and compared these with NZ’s largest food product by volume (milk), while ensuring that minimum dietary energy and protein requirements are met.

We found that the entire NZ population can be fed using 117,000 hectares of land and 5 million litres of liquid fuel a year if farming and transporting only wheat, as one example. Whereas 84,000 hectares and 12 million litres are required if relying only on potatoes. This compares to 640,000 hectares and 39 million litres if producing milk instead.

The liquid fuel required could be produced from canola oil, requiring 4,400 hectares of canola crop if producing wheat, 10,000 hectares for potatoes, and 32,000 hectares for milk.

If focusing on wheat, the land required for canola is only approximately 1 percent of currently grain cropped land in NZ. Canola also has the advantage of being frost resistant and therefore resilient in a nuclear winter.

Scenario 1: No trade, climate unchanged

Figure 1: Land area required for selected crops to feed the entire NZ population after a catastrophe ending liquid fuel imports but not changing the climate, and corresponding land area needed for biofuel feedstock

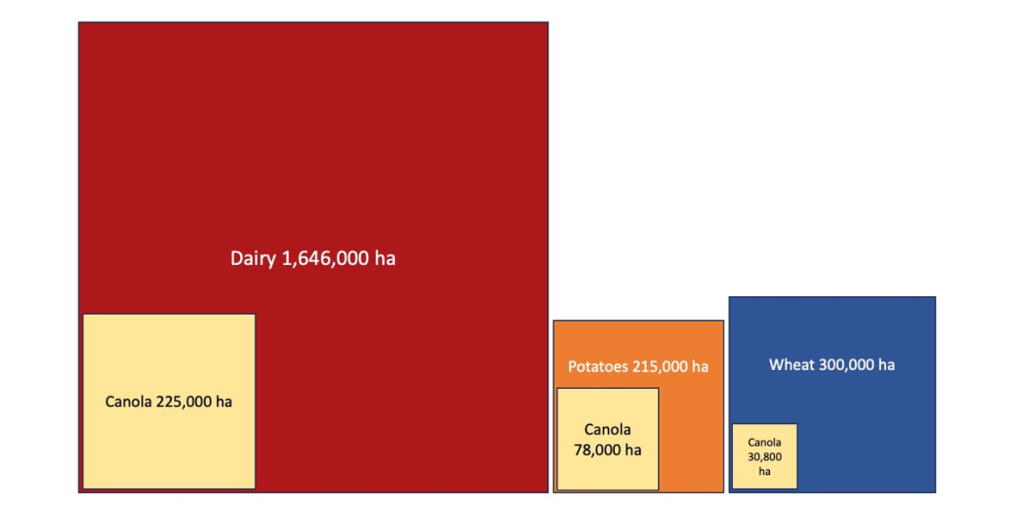

Scenario 2: No trade and severe nuclear winter

We also analysed the context of a nuclear winter where soot from nuclear explosions dims sunlight resulting in reduced crop yields. In a worst-case nuclear winter scenario (150 Tg soot in the stratosphere), minimum land area and canola crops as in Figure 2 would be needed.

Figure 2: Land area required for selected crops to feed the entire NZ population in a severe nuclear winter scenario, and corresponding land area needed for biofuel feedstock (assuming 150 Tg soot in the stratosphere and 100km average crop transport distance).

The main lessons are threefold:

- If a global catastrophe cuts liquid fuel supply then the ability to scale-up more efficient sources of food could extend the time that stored diesel supplies last

- The ability to scale-up production of biofuel feedstock such as canola could provide a sustainable supply of locally produced fuel in such circumstances…

- …if sufficient seed, and other inputs, and biofuel refining capacity has been anticipated in advance.

We analysed a post-catastrophe scenario, where many of the typical arguments against the production of biofuel crops do not apply. For example:

- In the context of a global catastrophe the feedstock would not displace food production, this or something similar would be necessary in New Zealand’s circumstances to allow food production (fuel for tractors etc).

- Our analysis does not require any new land to be cleared, merely judicious planting of existing agricultural land.

- Water and fertiliser use is basically unchanged because the land to be used is already cultivated.

- Considerations of carbon savings and lifecycle emissions are not the priority when whole populations may be at risk of starving.

Ensuring canola cultivation for food in normal times, along with sufficient biodiesel refining capacity, would allow for rapid scale-up of biofuel production in crisis times. This is a possible bridging solution for the next decades until widespread electrification of agriculture.

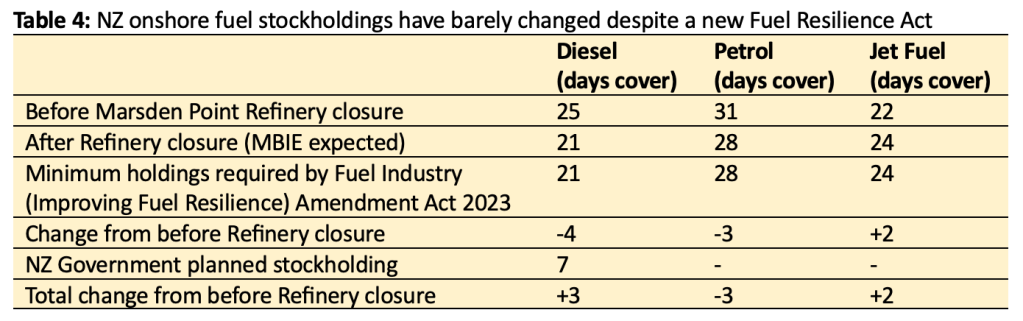

Current NZ Context

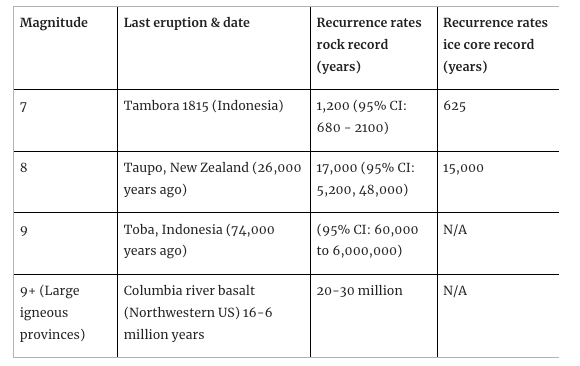

New Zealand is a remote island nation completely dependent on imports of liquid fuel for its agricultural production. There has been discussion in recent years about ideal volumes of onshore fuel holdings. However, despite much debate around new statutory requirements, there has been very little movement in actual holdings. Our 2023 report Aotearoa NZ, Global Catastrophe, and Resilience Options: Overcoming Vulnerability to Nuclear War and other Extreme Risks included the following table:

Original source: Terry, S (2023). Reimagining fuel resilience, and how to get it. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/reimagining-fuel-resilience-and-how-to-get-it

In preparing our 2023 report we surveyed and interviewed a wide range of experts. They described NZ’s reliance on oil refineries in the Northern Hemisphere such as in Singapore and South Korea and that these refineries in turn depend on producers such as Saudi Arabia. In a global conflict or crisis supply agreements could easily be reneged.

Interviewees recommended a revised NZ National Fuel Plan that details preparation for an extended no-fuel scenario. There is a need to calculate how much fuel is required, by whom, and for what, according to a population-level hierarchy of needs. There has been very limited planning for this so far.

Biofuels are clearly one possible part of the resilience response and a mechanism to stimulate local biofuel production would assist resilience. A mechanism that assisted biofuel production could provide biodiesel and potentially bunker fuel for shipping and the fishing industry; and appropriate biofuel for the military including the army, navy, and air force. The United States Navy has a biofuel mix strategy, and many OECD countries already have biofuel mandates.

A biofuel blend mandate was considered for NZ, but in a “policy bonfire” in February 2023, then Prime Minister Hipkins announced that the biofuels obligation would be discontinued. However, the coalition agreement between National and New Zealand First recognises the nation’s lack of fuel supply resilience and states that the government will undertake the following:

- Commission a study into New Zealand’s fuel security requirements.

- Investigate the reopening of Marsden Point Refinery. This includes establishing a Fuel Security Plan to safeguard our transport and logistics systems and emergency services from any international or domestic disruption.

- Plan for transitional low carbon fuels, including the infrastructure needed to increase the use of methanol and hydrogen to achieve sovereign fuel resilience.

- Ensure that climate change policies are aligned and do not undermine national energy security.

- Facilitate the development and efficiency of ports and strengthen international supply networks

Resources Minister Shane Jones has expressed concern about fuel security, stating that, “I feel it’s really important that we situate that what’s driving us is the resilience of our economy and the resilience of our nation” (Newsroom, 8 Feb 2024).

Fuel security should collectively concern the Ministers for Energy, Transport, Primary Industries, Civil Defence, Defence, and Climate Change. Climate emissions reductions and improved energy resilience are so interdependent that the respective plans for these should be developed side-by-side.

In fact, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment wrote to the Minister for Energy in December 2022, supporting the development of a whole-of-system Energy Strategy.

The above indicates government is now serious about security and that attention will next turn to what action is required. New initiatives are particularly salient given recent findings in the wake of Cyclone Gabrielle that NZ’s National Emergency Management Agency is ‘not currently fit for purpose’.

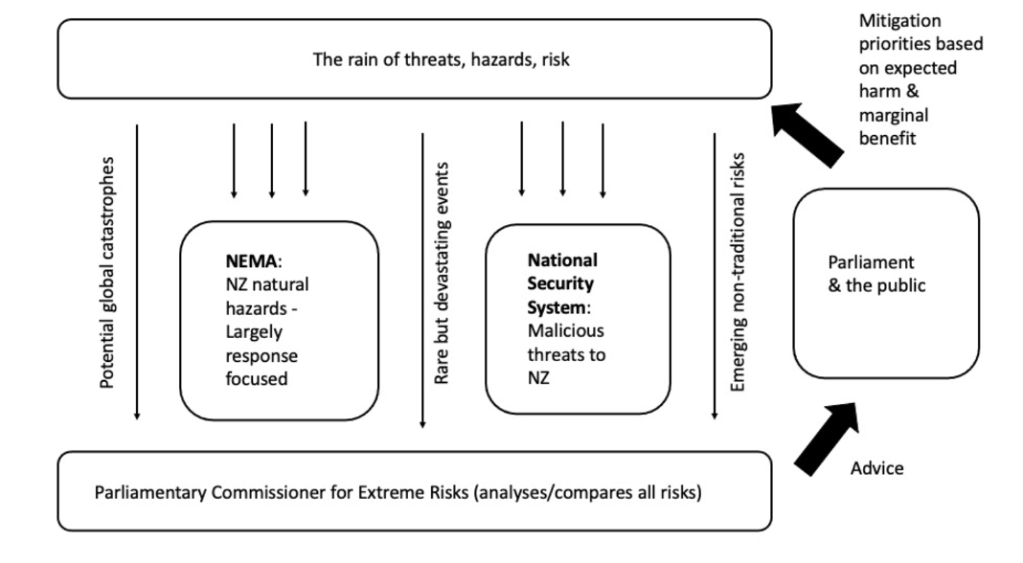

Actions Needed

Firstly, ongoing analysis is needed of the benefits and costs of various strategies. The DPMC’s list of nationally significant risks includes critical infrastructure failure, energy price shock, and major trade disruption, and the former Productivity Commission modelled a $250/barrel oil price shock in their report on Improving Economic Resilience. However, it appears that NZ Government agencies have not formally contemplated the impacts and mitigation measures for resilience to no-fuel scenarios, and where critical global infrastructure is destroyed, not merely disrupted.

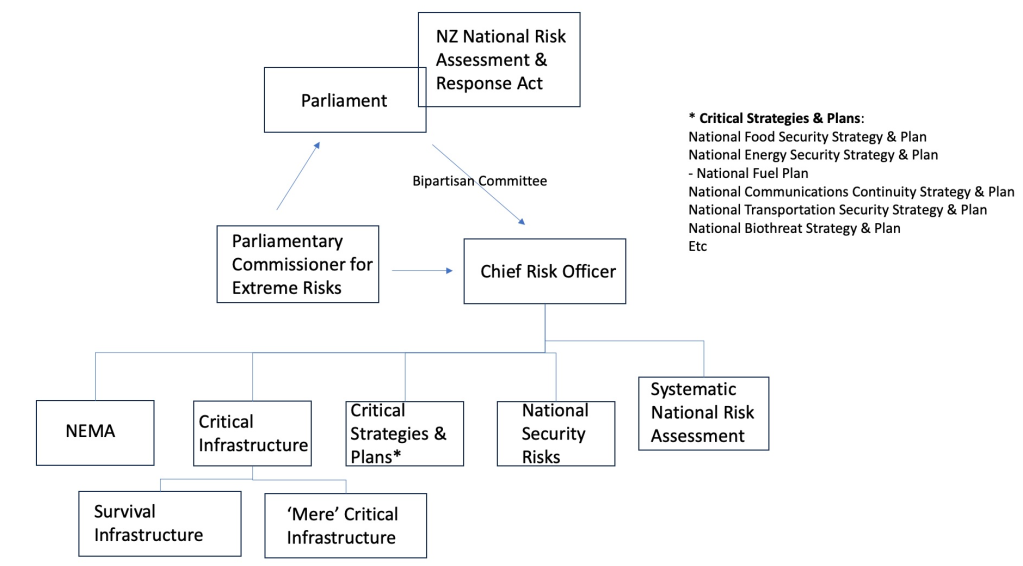

To insure against a global catastrophe NZ should:

- Develop a Fuels Resilience Plan that prioritises fuel for emergency and essential services – such as production of food and food transport.

- Determine the optimal mix of food crops to pivot production towards in a crisis, since crops like wheat and potatoes require far less fuel to feed the population than dairy (which consumes 7 times more diesel for the same food energy output as wheat).

- Identify and secure vital strategic national assets in pre-crisis times, such as wheat and canola seed, urban-adjacent cropping land, harvesting and processing infrastructure, and biofuel refining facilities.

- Consider preparatory investments in food system resilience, such as additional biofuel refining capacity and feedstock production.

- Develop a logistics plan for how to deploy these assets optimally within weeks to months should a catastrophe strike and pilot test this plan.

- Develop a National Food Security Plan and National Energy Security Plan that consider these issues in coordinated fashion.

- Conduct this kind of ‘worst case’ analysis across other sectors and services essential to survival.

- Recent analyses for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the Toda Peace Institute make the case for this catastrophe resilience work.

Policy needs to strike a balance between the capability to produce fuel in an emergency and optimising food production in normal times. Robust analysis should weigh the expected benefits of catastrophe preparedness and commercial revenues from canola (or other feedstock) products against the removal of it from use as a food. Other nations could also consider this kind of analysis.

See our just published paper Mitigating Imported Fuel Dependency in Agricultural Production: Case study of an island nation’s vulnerability to global catastrophic risks for a fuller discussion of these issues.