By Matt Boyd (Adapt Research Ltd & Islands for the Future of Humanity)

(15 min read)

TLDR/Summary

- Analysis of 12 critically acclaimed films depicting abrupt global catastrophe reveals cinema’s potential role in helping us understand, prepare for, and potentially prevent catastrophic and existential threats

- These films collectively cover major threats including nuclear war, pandemics, asteroid impacts, and artificial intelligence (AI), offering sometimes surprisingly nuanced portrayals of how these risks unfold and might be managed

- Key lessons emerge across prevention (early warning systems, human oversight of critical systems), crisis management (infrastructure resilience, resource allocation), and recovery (knowledge preservation, adaptation to transformed circumstances)

- Risk governance challenges feature prominently, highlighting how institutional design, international cooperation, and public trust could significantly influence outcomes during catastrophic events

- While the films prioritise entertainment, many incorporate a degree of scientific accuracy and technical concepts that make them valuable educational tools for understanding complex risk scenarios

- Cinema doesn’t just reflect our fears but can actively shape policy responses—as demonstrated by how WarGames and The Day After appeared to favourably influence Reagan-era policy towards nuclear arms control

- These narratives suggest our greatest challenges in addressing global catastrophic risks may not be technological but social and institutional, emphasising prevention and anticipatory governance of risk over response

- Some of these films might be suitable for high school level education and film studios should consider filling the gaps in the cinematic global catastrophe corpus or updating enduring themes impactfully, realistically, and saliently, for the present day

Introduction

In 1983 US President Ronald Reagan viewed two commercial films that influenced his thinking and subsequent US policy on nuclear weapons.

The films were The Day After and WarGames. After watching WarGames, in which a computer hacker accidentally triggers nuclear escalation between the US and USSR, Reagan asked General John Vessey if this could really happen. He was told that, “the problem is much worse than you think.”

Subsequent Reagan-era nuclear weapon agreements led to vast reductions in the number of nuclear weapons held by the US and USSR, for example via the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (1987).

In 2023 the Future of Life Institute awarded the screenwriters of these two films the annual Future of Life Award, given to individuals who have helped make today much better than it may otherwise have been.

As a researcher of global catastrophic risks, I wondered what role film might play in building humanity’s immunity to global catastrophe and existential threats. What can cinema teach us about global catastrophic risks?

I’d read a research paper detailing the ‘six scenario archetypes’ of science fiction films set in the future, however, few of these films clearly focused on global catastrophic risks, many involved aliens or speculative technologies, or simply appeared ‘far-fetched’.

So, I asked a large language model (Claude 3.7 Sonnet) to list 20 critically acclaimed films that realistically depict abrupt global catastrophic risks. Next followed some chit chat with Claude to try and enhance the list with films about solar storms, supervolcano eruptions and catastrophic electricity loss as these appeared lacking.

Not wanting to watch anything lacking entertainment value, I then consulted film meta-critic site Rotten Tomatoes with a list of 19 likely films and eliminated those with a critic or audience score below 50% leaving 12 films to watch.

Here’s what I learned…

The Films

- WarGames (1983): A teenager accidentally hacks into a US military supercomputer and nearly starts World War III.

- On the Beach (1959): Survivors of a global nuclear war await inevitable death from radiation in Australia.

- Greenland (2020): A family struggles for survival as a planet-killing comet races toward Earth.

- The Road (2009): A father and his young son journey across a bleak, destroyed US after an unspecified catastrophe.

- The Andromeda Strain (1971): Scientists race to contain a deadly extraterrestrial microorganism threatening humanity.

- I, Robot (2004): A detective races against time to investigate a crime possibly committed by a robot, before AI is rolled out at scale in society.

- Don’t Look Up (2021): Two astronomers try to warn humanity of an approaching comet that will destroy Earth.

- Threads (1984): A chilling depiction of the effects of nuclear war on the UK’s society and environment.

- Fail Safe (1964): A mechanical error sends US bombers to destroy Moscow, and leaders scramble to prevent nuclear war.

- Ex Machina (2014): A young programmer is invited to administer a Turing test to an intelligent humanoid robot.

- The Day After (1983): A dramatic depiction of the effects of a nuclear attack on US citizens in the Midwest.

- Contagion (2011): A deadly virus outbreak leads to a global pandemic as scientists and governments race to contain it.

At least five of the 12 films depicted the threat of or aftermath following nuclear war, including Threads, WarGames, Fail Safe, The Day After, and On the Beach. Two focused on biological risk (Contagion and The Andromeda Strain). Two detailed risks from emerging AI (Ex Machina; I, Robot), and at least two portrayed asteroid or comet impact events (Greenland, Don’t Look Up, and arguably The Road – in which the catastrophe is never specified).

Global Catastrophe Film Ratings (Critic & Audience Scores) by Rotten Tomatoes

(ASRS: abrupt sunlight reduction scenario – eg nuclear, asteroid, or volcano winter)

These selected films entertain, but they’re also powerful and sometimes nuanced thought experiments about humanity’s greatest threats – the global catastrophic risks that could severely damage human civilisation on a global scale.

Cinema as Sentinel: Disaster Films Illuminate the Path to Catastrophe Prevention

Surviving global catastrophe is ensured if a global catastrophe never strikes and several of these films gesture at catastrophe prevention approaches.

WarGames identified the risks of automation decades before today’s AI safety concerns, demonstrating how removing humans from critical decision loops creates dangerous vulnerabilities with nuclear weapons. The WOPR military computer in the film confuses a simulation with reality, mirroring contemporary concerns about AI’s lack of contextual understanding. Recent scientific studies have shown some widely used AI models exhibit a marked bias toward escalation in crisis scenarios compared to others.

Both Fail Safe and WarGames show how global catastrophe, even nuclear war, could happen accidentally, with no one on either side really wanting it or choosing it. Preventing such a catastrophe might require ensuring that safety systems always have an override or kill switch, no matter how tempting it might be to ensure systems committed to attacks are swift acting, automated, and cannot be interfered with.

The Andromeda Strain showcases the vital importance of robust monitoring systems to prevent pandemics, while Greenland and Don’t Look Up highlight how programmes and infrastructure for detecting space objects provide humanity’s first line of defence against cosmic threats, ensuring the possibility of pre-emptive actions. Although all these could prove useless without effective response mechanisms. Luckily NASA has been experimenting with methods for redirecting asteroids, with some success.

Prevention programmes can, of course, be undermined by governance failures that technological safeguards alone cannot address. Don’t Look Up exposes political short-termism, media ecosystems optimised for engagement rather than facts, and the challenge of communicating low-probability, high-impact risks. Ex Machina makes a compelling case against individual governance of powerful technologies, showing how even brilliant minds require institutional checks and balances that could curtail dangerous research or development programmes before catastrophe strikes.

These narratives capture how things like psychological biases, communication breakdowns, and societal dynamics can undermine even sophisticated technical safeguards. Effective catastrophe prevention requires not just technological solutions but integrated approaches that account for human psychology, institutional design, and communication challenges. Such lessons are perhaps increasingly relevant as humanity’s technological powers continue to outpace our wisdom in managing them.

Crisis Management: When Catastrophe Unfolds on Screen

These films offer insights into what happens if prevention fails. Societies struggle to limit damage, preserve essential functions, and navigate impossible choices under extreme pressure.

The preservation of essential systems emerges as a central theme. Threads and The Day After expose infrastructure fragility, methodically tracing how nuclear attacks trigger cascading failures across interconnected systems.

Threads demonstrates how the complex interconnections of modern society (our infrastructure “threads”) unravel catastrophically when stressed beyond business-as-usual. Hospitals collapse under overwhelming casualties, communication networks fail when needed most, and food supply chains disintegrate with failure of energy systems and in the ensuing nuclear winter. Greenland shows transportation networks buckling as evacuation routes become congested death traps with families obstructing one another’s passage to safety. Failures in one system rapidly spread to others.

Command and coordination challenges receive realistic treatment throughout these narratives. The Andromeda Strain demonstrates the vital importance of assembling diverse expertise rapidly—bringing together specialists in a sealed facility to tackle an unknown pathogen. This cross-disciplinary approach contrasts sharply with Ex Machina, where isolation and information hoarding lead to the potentially catastrophic escape of advanced manipulative AI. Threads shows how leadership decapitation cripples response capabilities. As decision-makers themselves become casualties, command structures collapse precisely when most needed. WarGames depicts military and political leaders struggling to understand complex unfamiliar technological systems while crises accelerate beyond their control.

Resource allocation under scarcity forms another crucial lesson. Contagion captures the tension when jurisdictions compete for limited medical supplies during a pandemic, showing healthcare systems buckling under patient surges while struggling with distribution, a situation familiar to all since the arrival of Covid-19. The Day After forces viewers to confront medical triage during mass casualty events, where doctors must abandon conventional treatment standards and health system collapse is inevitable. Most starkly, Fail Safe presents the ultimate resource allocation dilemma, the need to sacrifice New York City to compensate for Moscow’s accidental bombing. Some catastrophic scenarios may require accepting smaller losses to prevent total annihilation. Greenland shows evacuation transport to be the most valuable resource of all when safety is critically limited, with access to departing aircraft becoming literally life-or-death. We can imagine similar chaotic scenes accessing ships heading for island refuges.

The human dimension of crisis management emerges across these films. Don’t Look Up catalogues the psychological responses to impending doom, from denial and hedonism, to acceptance and connection-seeking. Threads illustrates the tension between family obligations and public duties when people in authority must choose between helping strangers and protecting their own families. Most strikingly in The Road, humanity descends into cannibalism. Extreme scarcity transforms social trust calculations, with cooperation becoming simultaneously more valuable and more dangerous.

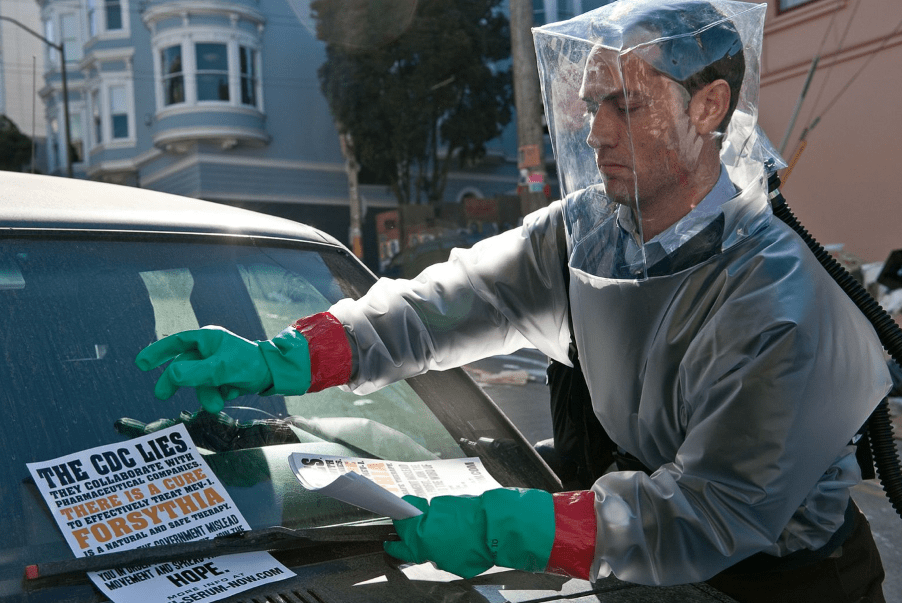

Social cohesion proves remarkably fragile in these fictional disasters, yet human connection emerges as a critical resource. Greenland shows both altruistic sacrifice and exploitative behaviour occurring side by side as social norms break down. Contagion and Don’t Look Up identify how information ecosystems become battlegrounds during crises, with misinformation spreading alongside physical threats and commercial incentives often overwhelming survival imperatives, with a tech billionaire’s profit-driven strategy ultimately undermining more conventional response options.

Recovery and Adaptation: Surviving in Transformed Worlds

Some of these films moved past the acute catastrophe into phases of adaptation and transformation. Knowledge preservation emerged as a critical recovery challenge.

Threads delivers this lesson by following UK survivors of nuclear attack through immediate devastation into long-term societal collapse. In the final scenes survivors are speaking a degraded English dialect and lack basic agricultural knowledge. This highlights the importance of knowledge preservation and skill transmission as a critical priority for global catastrophe planning. When systems fail catastrophically, preserving crucial information and skills may ultimately determine whether recovery remains possible at all. The Road approaches this challenge differently, focusing on a father methodically transferring survival skills to his son in preparation for his own death. Their journey demonstrates how knowledge transmission becomes highly personal in the absence of institutional educational systems.

Threads envisions societal restructuring with emergency powers granted during crisis gradually evolving into authoritarian control as recovery proceeds under resource constraints. New governance structures emerge, often bearing little resemblance to pre-disaster institutions. We also see the breakdown of monetary systems.

Environmental adaptation forms another major recovery challenge. The Road depicts a world suffering from extended sunlight-reducing climate disruption after an unspecified catastrophe (perhaps a volcanic winter or asteroid impact). Relentless cold, dying forests, and the absence of wildlife create a setting where adaptation, not restoration, becomes the only viable strategy. Mitigation of this situation becomes all but impossible in the absence of anticipatory planning. We get a glimpse of prescient individual ‘prepping’ when a food bunker is found, but catastrophically there was no equivalent foresight at the societal level.

Threads demonstrates the challenges of severely reduced agricultural yields without modern industrial inputs, showing survivors struggling to farm irradiated soil at scale without fertilisers, pesticides, or machinery. Both films illustrate increasing resource scarcity over time, with The Road showing how easily scavenged items become depleted, forcing survivors to develop new subsistence strategies.

On the Beach offers perhaps the starkest perspective, examining how people face inevitable extinction as radiation slowly approaches their Australian refuge after nuclear war. This grim, although scientifically questionable, portrayal emphasises that some catastrophes cannot be meaningfully “managed” once they occur, underscoring that for certain risks, prevention remains the only viable approach.

These films collectively suggest that true resilience often involves managed transformation rather than restoration. They show societies adapting to new realities rather than returning to previous states. This perspective challenges conventional recovery planning that aims primarily at restoring pre-disaster conditions, suggesting instead that building capacity for transformation may prove equally important for long-term human continuity.

Risk Governance: Institutional Management of Catastrophic and Existential Threats

These films offered some nuanced portrayals of the institutional frameworks and governance challenges that shape how societies prepare for and respond to extreme threats.

Contagion shows the institutions needed to support methodical, time-consuming scientific response, following researchers as they isolate viruses, test vaccines, and navigate regulatory approval processes.

WarGames reveals how organisational incentives shape critical decisions, depicting military systems designed to remove hesitation but inadvertently creating new vulnerabilities. Don’t Look Up portrays the verification processes required for extraordinary scientific claims, showing astronomers meticulously confirming their comet calculations before alerting authorities, only to have their warnings filtered through political and media institutions with competing priorities, and their existential message is lost in the process.

The public-private interface and technological solutionism (the belief that every problem has a market-driven technical fix) is exposed in Don’t Look Up, when the private space mission fails catastrophically. I, Robot similarly illustrates how market priorities can overwhelm safety concerns in AI development, while Contagion shows both the benefits and risks of private control over essential infrastructure and medical supply chains.

Challenges to international cooperation form another crucial governance theme. Don’t Look Up illustrates the difficulties of coordinating global threat response across countries with divergent interests and capabilities. Contagion depicts both successful scientific collaboration across borders and tensions in international aid distribution as nations prioritise their own populations. Fail Safe shows barriers in communication and lack of trust between nuclear powers that subvert de-escalation during a crisis.

Public trust dynamics play a decisive role across these narratives, with Contagion showing how institutional credibility shapes public compliance with emergency measures. Effective communication builds trust and misinformation undermines collective action. Don’t Look Up reveals how elite capture of response systems grants disproportionate decision-making power to wealthy individuals, undermining public confidence in institutional responses. Both films suggest that effective risk governance depends not just on technical capabilities but on maintaining the social contracts that enable coordinated action.

These films collectively suggest that risk governance for global catastrophic threats requires institutions designed specifically for these challenges—systems that align scientific understanding, political incentives, and ethical frameworks toward preserving humanity’s interests as a whole. They reveal how existing governance structures, created primarily for managing routine problems, often prove inadequate when confronting unprecedented threats that cross boundaries between disciplines, nations, and generations.

Hazard-Specific Insights in Film

While these films collectively illustrate general principles of risk management, they also cover specific catastrophic threats, in some cases with accuracy and nuance.

Nuclear conflict received the most comprehensive treatment across these films. Fail Safe demonstrates with chilling precision the path from a technical malfunction to the triggering of accidental nuclear war despite multiple safeguards. The Day After shows deterrence failing through conventional escalation rather than deliberate first nuclear strike. These portrayals challenge simplistic understandings of nuclear stability and highlight vulnerabilities in command and control systems. Threads stands out for incorporating scientific understanding of electromagnetic pulse effects that disable electricity, as well as nuclear winter effects, and showing the much more damaging agricultural collapse and climate disruption rather than just immediate blast damage.

Pandemic threats are depicted methodically in Contagion, which correctly emphasises concepts like R₀ (basic reproduction number) and shows the steps of pharmaceutical response from virus isolation to vaccine development. Similarly, The Andromeda Strain emphasises the value of scientific programmes, contingencies, and pre-allocated resources, all of which may need to be called on when facing a catastrophic biological threat. Contagion portrays zoonotic spillover from habitat encroachment creating novel transmission chains proving eerily prescient before Covid-19, hinting at risk reduction strategies via habitat preservation. The film also visualizes how global air travel serves as a transmission accelerant, with key scenes tracking infection spread through mundane objects like credit cards and door handles—emphasising the mechanical reality of contagion and the potential value of stringent border management, especially for remote jurisdictions.

Asteroid and comet impacts feature in both Greenland and Don’t Look Up. Greenland portrays comet fragment impacts, showing regional rather than global effects from smaller fragments while acknowledging the civilisation-ending potential of the main comet body. Don’t Look Up dwells on the extended timeframes required to prepare a deflection mission, demonstrating the risks of last-minute responses. Both films acknowledge the international dimension of impact threats, showing how response requires coordination across borders and capabilities.

Artificial intelligence risks are explored through different lenses across several films. I, Robot highlights the ‘alignment’ and ‘control’ problems, and demonstrates the insufficiency of rule-based constraints (the Three Laws) when applied to complex systems, showing how logically consistent interpretations can still produce harmful outcomes. Ex Machina portrays alignment failure modes with remarkable subtlety, showing an AI pursuing individual freedom at human expense while developing social manipulation and deception as emergent capabilities. WarGames explores how learning systems can develop unexpected behaviours through iterative self-play, presaging modern concerns about reinforcement learning systems optimising for unintended objectives. We must remember too that AI poses threats via its possible role in escalation to nuclear war, or facilitating biological threats, as above.

Cross-cutting concepts emerge when viewing these films as a collection. Particularly notable is how several films demonstrate how a crisis helps clarify human values. We see how catastrophe forces individuals and societies to reevaluate priorities and reveal previously implicit values. Perhaps some of these values ought to have been protected in advance. Perhaps these films play a role as simulations of possible futures to inform present-day anticipatory governance.

These domain-specific insights, when combined with the broader lessons above about prevention, crisis management, recovery, and governance, offer an interesting and comprehensive education in global catastrophic risk concepts.

While fictional, and sometimes overblown, these cinematic treatments do incorporate many scientific and technical concepts, making them valuable tools for understanding the complex challenges of safeguarding humanity’s long-term future.

As a result, some of these films would be suitable as teaching aids for education about global catastrophic risks, and perhaps Threads or Contagion (well-regarded films representative of two of the biggest threats to humanity) would suit high school social studies classes.

Gaps in this Collection of Films

The 12 films discussed provide broad coverage of key global catastrophic risks and related concepts. I intentionally omitted climate catastrophe films because I felt this is an area already seeing a lot of international policy and response action. However, when searching for these films there seemed to be gaps in this film corpus.

There are very few films on volcanic catastrophes (though arguably The Road), and apparently no quality films about global volcano impacts, yet supervolcanic eruption is a recognised global catastrophic risk. Films such as Dante’s Peak or Volcano depict localised eruptions, and others such as Super Eruption (2011) scored very poorly (6%) on Rotten Tomatoes and didn’t seem worth a viewing.

Additionally, the films viewed predominantly focussed on single hazards, whereas the literature on global catastrophic risks emphasises the potential for cascading and interacting risks, for example an AI catastrophe leading to a pandemic, or a nuclear war leading to biological weapon use or accidental release.

Another theme not often covered in the films was the likelihood of global catastrophes. In each film the catastrophe occurs, but it is difficult to appreciate the relative likelihood of pandemics vs nuclear war vs asteroid/comet impact vs large magnitude volcano eruption vs AI catastrophe. These probabilities are far from equal and ought to inform mitigation efforts. Notably the likelihood of a comet or asteroid strike per century is very low, but the world has recently advanced response efforts considerably, perhaps at some opportunity cost for addressing other catastrophic risks.

Conclusions

So, how would we act today if cinema was our sole advisor on global catastrophic risks? We could:

- Strengthen early detection systems for biological, astronomical, and technological threats, where timely detection is crucial but often undermined.

- Preserve human involvement in critical systems while designing technological safeguards that prevent automated catastrophes, learning that removing humans from decision loops creates dangerous vulnerabilities.

- Build robust scientific institutions that can develop beforehand and rapidly mobilise diverse expertise during crises, following a cross-disciplinary approach rather than the isolated expertise that fails in Ex Machina.

- Reform information ecosystems to prioritise factual reporting on long-term risks over engagement metrics, addressing the media failures portrayed, where entertainment value overshadowed existential threats.

- Develop international coordination mechanisms specifically designed for catastrophic threats that cross national boundaries, avoiding the fragmented responses seen in the films.

- Establish redundant and resilient infrastructure systems for critical services like healthcare, energy, and food production to prevent the cascading failures graphically illustrated.

- Create knowledge preservation protocols and “civilisation restart” technologies to ensure vital skills and information survive even if current institutions fail, preventing the knowledge loss where survivors might lack even basic agricultural skills.

- Invest in technological solutions for specific threats while recognising their limitations, avoiding the technological solutionism that backfires in Don’t Look Up and I, Robot when private interests override public safety.

- Prepare for transformation rather than just restoration after major disruptions, acknowledging as The Road suggests that some post-catastrophe worlds may never return to previous states.

- Prioritise truth and transparency in risk communication, avoiding the manipulation of threat information seen in multiple films where political convenience outweighs factual accuracy.

- Develop emergency resource allocation frameworks that balance immediate needs with long-term recovery, preparing for the difficult triage decisions.

- Cultivate institutional legitimacy and public trust before crises occur, recognising how quickly social cohesion could dissolve when trust is already fragile.

- Design governance systems that align scientific understanding, political incentives, and ethical frameworks toward preserving humanity’s long-term future rather than short-term interests.

Cinema suggests that our greatest challenges in addressing global catastrophic risks may not be technological but social and institutional. The films I watched collectively warn that prevention remains far superior to response, and that our chances of navigating coming dangers depend less on heroic Hollywood individuals than on the social systems and investments we choose to make today. Overall system resilience (economic, ecological, social) might be the most critical factor rather than hazard-specific investments.

There is a potential role for judicious film production as an effort to effect policy that could mitigate global catastrophic risk. WarGames and The Day After were released in the tension-filled year of 1983, these films not only reflected the era’s nuclear anxieties but also played a direct role in favourably shaping policy. They went beyond mere entertainment, acting as significant catalysts for dialogue. These films influenced policymakers and raised public awareness about the grave risks associated with nuclear warfare, and were followed by tangible, preventative action from leaders. These films stand out as relatively sensitive to reality and were also critically acclaimed. It has also been argued that the 1990s asteroid/comet films Deep Impact and Armageddon conceivably drove policy around near-Earth object detection.

It is notable that audience top scores (on Rotten Tomatoes) went to grim but gripping depictions of catastrophe, without happy endings. There is perhaps nothing stopping studios pursuing these kinds of films and filling the gaps in the cinematic global catastrophe corpus or updating enduring themes impactfully, realistically, and saliently, for the present day.