By John Kerr, Matt Boyd, & Nick Wilson (Blog crossposted from PHCC ‘the Briefing‘)

TLDR/Summary:

There is increasing concern over catastrophic threats such as nuclear conflict, engineered pandemics, and emerging technologies including artificial intelligence. Our just published survey research shows New Zealanders want their government to take these risks seriously. Majority public support for planning and strategy on risks underscores the need to move beyond analysis and invest in practical preparedness. Yet Aotearoa New Zealand remains underprepared, with vulnerabilities in areas such as energy security and industrial inputs needed for food production.

Building resilience will require more than technical planning: trusted communication, cross-sector leadership, and public engagement are vital to maintain legitimacy and consensus. The findings highlight a need for policymakers to align with public expectations by developing a national strategy, strengthening institutions, and broadening the voices involved in planning for worst-case scenarios.

Introduction

Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), like all nations, faces the possibility of extreme events that could cause global or civilisation-level disruption. These global catastrophic risks include nuclear conflict, bioengineered pandemics, major volcanic eruptions, severe space weather, and potentially runaway artificial intelligence (AI). While the probability of any one event is low in a given year, the potential consequences are so severe that preventive efforts and proactive planning are essential.1, 2

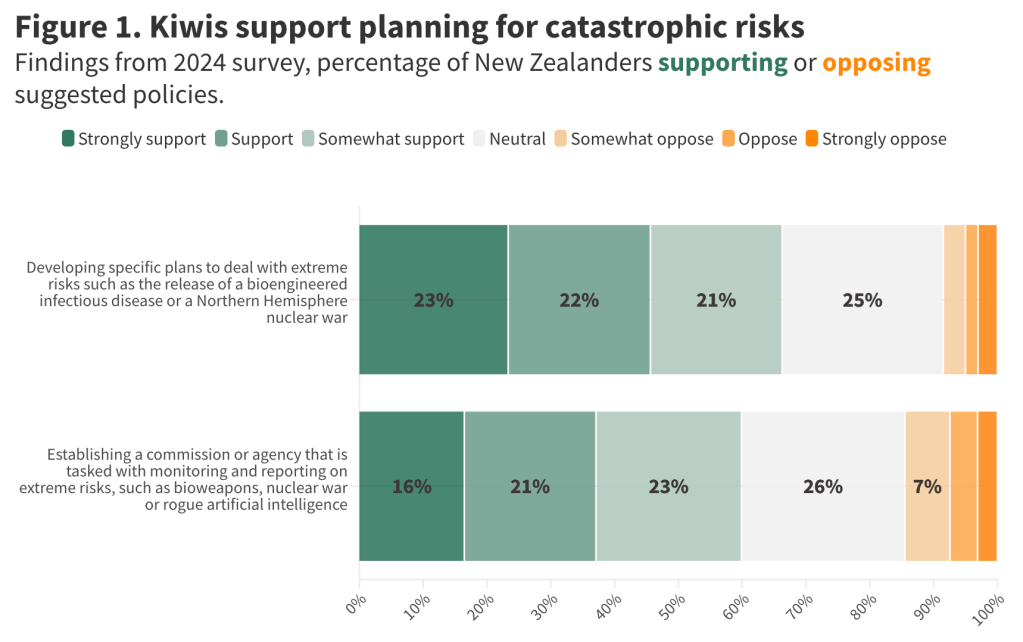

Our survey of more than 1,000 New Zealanders provides evidence on how the public views government responsibility for these risks (Figure 1). The results, published in the journal Risk Analysis, show majority support for greater action – but also raise questions about gaps in trust, communication, and institutional readiness.3

Key Findings from the Survey

- Two-thirds of New Zealanders (66%) support government developing specific plans for catastrophic risks such as nuclear war or engineered pandemics.

- A clear majority (60%) also back establishing a dedicated commission or agency to monitor and report on these risks.

- Outright opposition is small (8–15%), but about a quarter of respondents are neutral or unsure, suggesting limited awareness or competing priorities.

- Support for government planning increases with age, education, income, and trust in scientists.

- Unlike many public health issues, there were no major differences in policy support across political orientation, gender, or ethnicity.

Overall, this suggests majority support across the political spectrum for government leadership on catastrophic risks. Trust in science stands out as the strongest predictor of support, highlighting both an opportunity and a vulnerability for building consensus.

Why this Matters Now

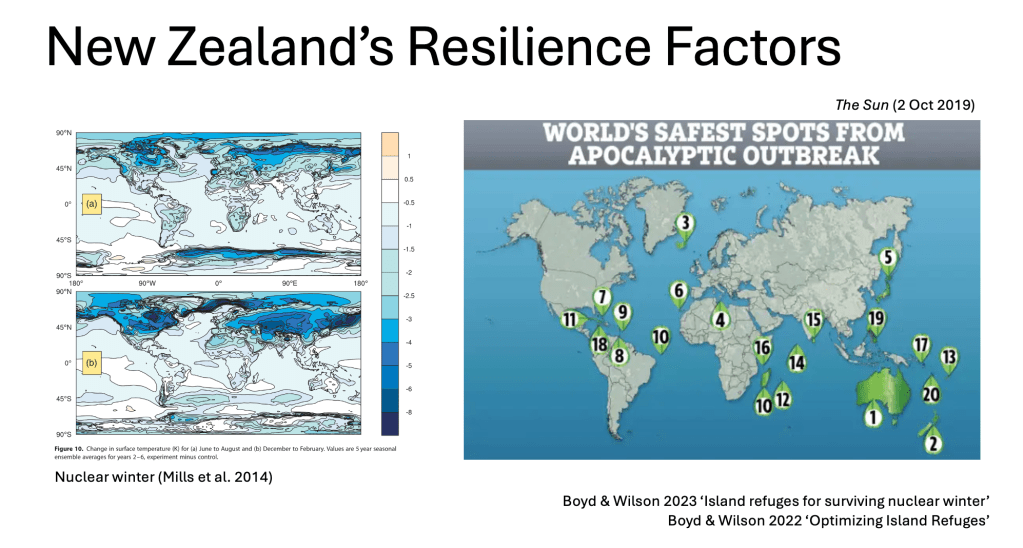

Although NZ has previously examined catastrophic risks – for instance, through work in the 1980s on nuclear war4, 5 – resilience has waned. Recent expert reviews conclude that Aotearoa remains poorly equipped to cope with global shocks, despite being relatively well placed geographically to weather them.6, 7

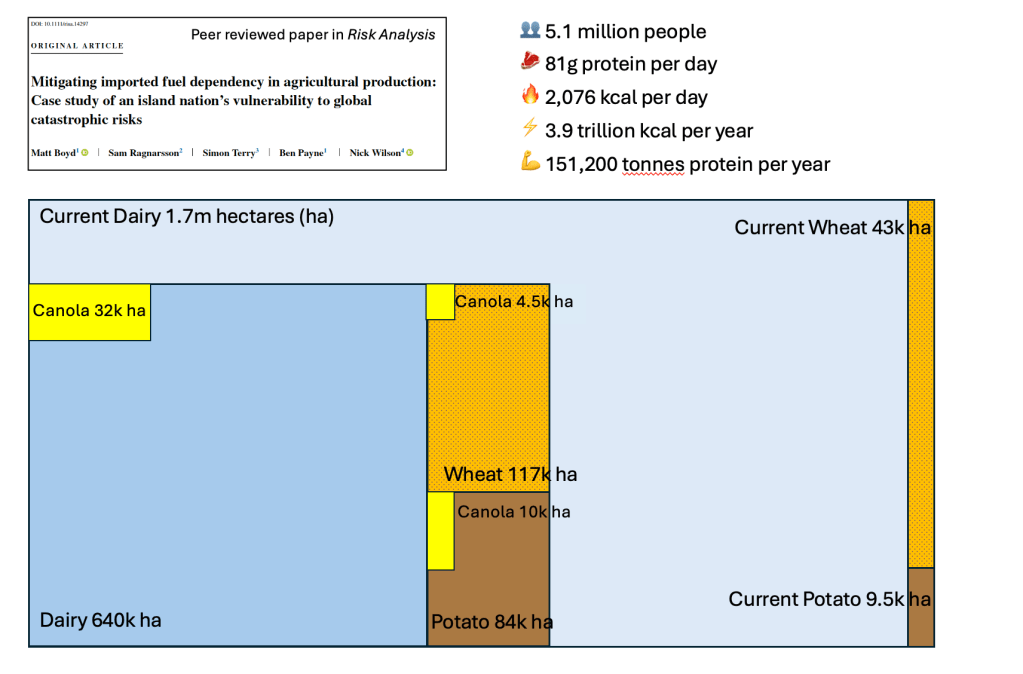

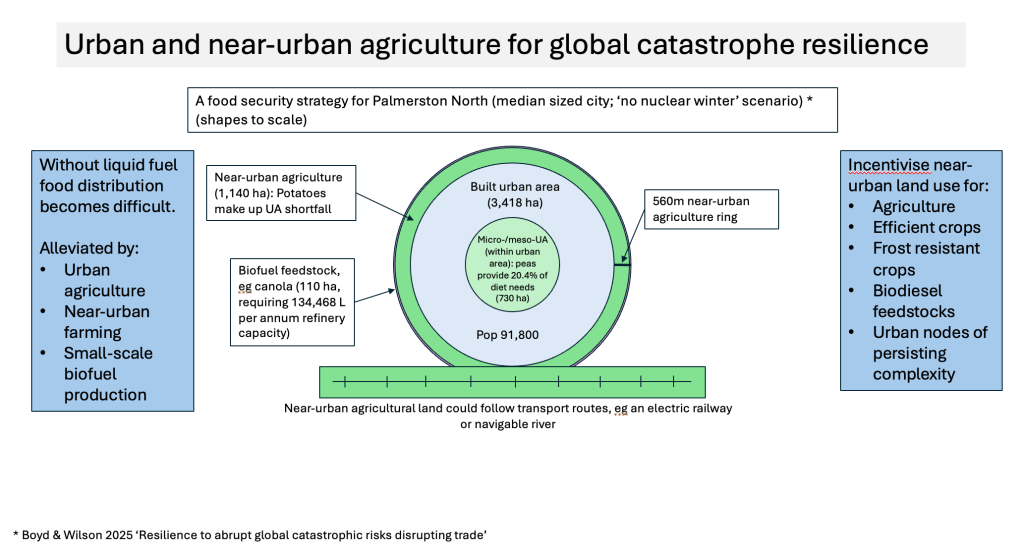

The contrast between strong public support and limited government preparedness is striking. In a 2021 review, Sir Peter Gluckman and Dr Anne Bardsley highlighted major gaps in national planning for high-impact risks.8 More recent work has shown vulnerabilities such as reliance on imported fuel for food production, despite NZ’s apparent self-sufficiency in food supply.6, 9

This new survey reinforces earlier evidence. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s 2024 National Risks Public Survey found overwhelming support for government responsibility in managing threats from emerging technologies and critical infrastructure disruption.10 Our findings extend this picture, showing that the public also endorse forward planning for the very worst-case scenarios.

Understanding Ambivalence and Opposition

A significant minority of New Zealanders remain neutral or opposed to stronger government action. Possible reasons11 include:

- Low awareness of catastrophic risks and their likelihood.

- Fatalism – a belief that little can be done to prepare.

- Distrust in government or science as credible actors.

- Competing priorities, with attention focused on more immediate social and economic concerns.

This points to the need for broader engagement beyond surveys. Deliberative methods such as citizens’ assemblies, public forums, and focus groups could help unpack how people weigh catastrophic risk planning against other policy demands, and identify framings that resonate across diverse groups.

Trust as a Foundation

The finding that trust in scientists is the single most consistent predictor of support is particularly important. While scientists are central to identifying and communicating extreme risks, they are not always the most effective messengers. For people with low trust in science, other credible voices – such as iwi leaders, community representatives, or political figures across the spectrum – may be more effective in building support.

This echoes lessons from public health communication during the Covid-19 pandemic, where trust was both an asset and a fault line. Building a coalition of trusted messengers will be vital for gaining broad consensus on preparedness.

Policy Implications

The survey adds to mounting evidence that NZ needs to go beyond the hazards it currently plans for (earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and severe space weather) to address all major catastrophic risks. Several policy options merit urgent consideration:

- Develop a national strategy for global catastrophic risks – building on the National Risk Framework but extending it to worst-case scenarios.8

- Establish a dedicated agency or commission, either domestic or in partnership with Australia12, to monitor, assess, and coordinate responses to these risks.

- Invest in resilience measures that reduce vulnerabilities exposed in recent studies, such as energy security for ensuring food production.9, 13

- Engage the public through deliberative processes to deepen understanding of trade-offs and maintain legitimacy.

- Broaden communication approaches, pairing scientific expertise with trusted community and political voices.14, 15

Moving from Analysis to Action

As we noted in an earlier PHCC briefing on the NZ Government’s work on hazards16, progress has been made in recognising some major threats, but important gaps remain.

NZ’s geographic position makes it one of the countries most likely to endure in certain global catastrophes. But survival advantage will only matter if we have invested in resilience and governance structures in advance. Public opinion is clear: most citizens want government to prepare for the unimaginable, before it is too late.

What is New in this Briefing?

- Risk scholars and other experts are increasingly concerned about the high-impact threats of global catastrophic risks such as severe engineered pandemics, nuclear war and rogue AI.

- The majority of New Zealanders support broad Government action to plan for global catastrophic risks.

- Few New Zealanders are actively opposed to policies addressing catastrophic risks, however a quarter (~25%) are unsure or ambivalent.

Implications for Policy and Practice

- More in-depth research is desirable to understand why some people are unsure or opposed to Government action.

- Nevertheless, it is now over to policymakers to respond to the majority public support for better Government planning and infrastructure to identify and prepare for global catastrophic risks.

References

- Mecklin J. (2025). Closer than ever: It is now 89 seconds to midnight – 2025 Doomsday Clock Statement. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/2025-statement/

- World Economic Forum. (2025). The Global Risks Report 2025. https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2025/

- Kerr J, Boyd M, & Wilson N. (2025). Public Attitudes to Responding to Global Catastrophic Risks: A New Zealand Case Study. Risk Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.70096

- Preddey G, Wilkins P, Wilson N, Kjellstrom T, & Williamson B. (1982). Nuclear Disaster: A Report to the Commission for the Future. https://www.mcguinnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/CFTF-March-1982-Future-Contingencies-4-Nuclear-Disaster-FULL.pdf

- Green W, Cairns T, & Wright J. (1987). New Zealand After Nuclear War. New Zealand Planning Council.

- Boyd M, Payne B, Ragnarsson S, & Wilson N. (2023). Aotearoa NZ, Global Catastrophe, and Resilience Options: Overcoming Vulnerability to Nuclear War and other Extreme Risks: Report by the Aotearoa NZ. Catastrophe Resilience Project (NZCat) [Report]. Reefton: Adapt Research Ltd. https://adaptresearchwriting.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/231117-v1-nzcat-resilience-nuclear-gcrs-1.pdf

- Boyd M, & Wilson N. (2021). Anticipatory Governance for Preventing and Mitigating Catastrophic and Existential Risks. Policy Quarterly, 17(4), 20-31.

- Gluckman P, & Bardsley A. (2021). Uncertain but inevitable: The expert-policy-political nexus and high-impact risks. https://informedfutures.org/high-impact-risks/

- Wilson N, Prickett M, & Boyd M. (2023). Food security during nuclear winter: A preliminary agricultural sector analysis for Aotearoa New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online), 136(1574), 65-81.

- Ipsos. (2024). National risks public survey: All threats and hazards (Commissioned by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet). https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/risk-and-resilience/national-risk-framework/2024-national-risks-public-survey-report

- Wiener JB. (2016). The Tragedy of the Uncommons: On the Politics of Apocalypse. Global Policy, 7(S1), 67-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12319

- Wilson N, Boyd M, Potter J, Mansoor O, Kvalsvig A, & Baker M. (2024). The case for a NZ-Australia Pandemic Cooperation Agreement. Public Health Expert Briefing. https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/case-nz-australia-pandemic-cooperation-agreement.

- Boyd M, Ragnarsson S, Terry S, Payne B, & Wilson N. (2024). Mitigating imported fuel dependency in agricultural production: Case study of an island nation’s vulnerability to global catastrophic risks. Risk Analysis https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14297.

- Johns Hopkins University. (2019). Risk Communication Strategies for the Very Worst of Cases. https://centerforhealthsecurity.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/190304-risk-comm-strategies.pdf

- Balog‐Way D, Mccomas K, & Besley J. (2020). The Evolving Field of Risk Communication. Risk Analysis, 40(S1), 2240-2262. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13615

- Wilson N, Kerr J, & Boyd M. (2025). New government document on hazards: Good progress but gaps remain. Public Health Expert Briefing. https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/new-government-document-hazards-good-progress-gaps-remain