An in-depth read, ~15 min

TLDR/Summary

- Global systems theorist Thomas Homer-Dixon gave a webinar on Nov 6, 2025 in which he described the Cascade Institute’s breakthrough approach to modelling global systemic risk. You can watch the full video of his presentation on the ASRA YouTube channel.

- The Polycrisis Core Model (PCM) is a sophisticated analytical tool that not only maps the complex interactions driving today’s global crises but could help identify concrete pathways toward more hopeful futures.

- Moving beyond speculation: Previously, ideas about achieving positive global transformation were largely speculative. Now, based on 1,800 expert judgments and rigorous mathematical modelling, there’s a grounded, evidence-based approach to understanding how we might navigate out of today’s entangled crises.

- The PCM uses Cross Impact Balance (CIB) analysis to model 11 global subsystems (covering everything from economy and climate to food and governance), each with multiple possible states, generating over 4 million potential future scenarios for humanity by 2040.

- Only 11 scenarios are truly stable: Out of 4 million possibilities, the mathematics reveals just 11 “consistent” scenarios, or attractors in an 11-dimensional state space. Three major attractors emerge: Illiberal Decline, Mad Max, and Hope.

- The Hope attractor exists but is narrow: The good news is that a positive future is mathematically possible. The challenging news is that Hope attracts only about 100,000 scenarios compared to Mad Max’s 500,000, and it remains climatically “Hot” (high degrees of global warming), these facts mean resilience work against collapse remains a critical hedge.

- Democracy appears non-negotiable: The analysis reveals clear policy targets which most notably include maintaining democracy, this appears essential for any pathway to Hope. Without democratic systems, initial modelling suggests no viable route to positive outcomes.

- The work is actionable, not academic: The model identifies specific leverage points for interventions and provides a framework for understanding which policy moves might push us toward the edge of Hope’s basin of attraction, where natural system dynamics would pull us in to a positive future.

Introduction: Can We Model Our Way to Hope?

On November 6, 2025, Thomas Homer-Dixon presented findings from the Cascade Institute’s Polycrisis Core Model to a webinar hosted by the Accelerator for System Risk Assessment (ASRA). The presentation offered something rare in discussions of global catastrophic risk: not just a diagnosis of our predicament, but the potential for a mathematically grounded pathway through it.

This matters because, as Homer-Dixon emphasised, previously speculative ideas about reaching hopeful futures are now grounded in modelling and evidence. Based on approximately 1,800 expert judgments, the work demonstrates a concrete way to navigate toward hope, or at least to understand the terrain we must cross.

The timing is significant. As I reported in my recent blog on the ASRA Symposium, humanity faces accelerating, amplifying, and interacting crises across interconnected global systems. This polycrisis isn’t theoretical it is the world’s lived reality of pandemics, climate change, geopolitical conflict, economic instability, and democratic backsliding all reinforcing one another. For a New Zealand perspective on this see our recent paper on long-term resilience to global risk.

What the Cascade Institute’s new Polycrisis Core Model (PCM) offers is the potential for a way to move from acknowledging this complexity to actively navigating it.

The Cascade Institute’s Approach

The Cascade Institute has focused its work on identifying high-leverage interventions in global systemic risk. Their CORE initiative examines what pathways exist toward better futures through rigorous systems analysis.

The PCM represents the latest evolution of this work. As Homer-Dixon explained in the webinar linked above, it builds on the legacy of the “Limits to Growth” report (which Homer-Dixon called “the granddaddy of world models”) but employs more sophisticated methods suited to understanding social and political systems where relationships are inherently fuzzier than in physical or ecological models.

The CORE Model’s ambition is substantial: to create a “global system-of-systems” analysis projecting to 2040, capable of mapping millions of possible futures and identifying which are self-reinforcing (and therefore stable) and which policy interventions might shift humanity’s trajectory away from worse world states and into more hopeful ones.

Crucially, this isn’t just descriptive work. The model aims to identify plausible pathways to positive transformation, or what Homer-Dixon called finding the “self-reinforcing virtuous processes” that could move us toward flourishing world states rather than collapse.

The Technical Architecture: How the Model Works

For those comfortable with complexity science, the PCM employs Cross Impact Balance analysis (see below). But Homer-Dixon’s presentation makes the core methodology accessible to non-specialists.

The Building Blocks: 11 Subsystems, 45 States

The model divides global systems into 11 subsystems, split between social and material domains. Each descriptor can exist in one of 3-5 possible states across time. This creates the model’s vast scenario space:

Social subsystems (5):

- Economy (states: laissez-faire growth, guided growth, low growth, managed economic contraction, unmanaged economic failure)

- Polity Type (states: strong democracy, illiberal democracy, strong autocracy, weak autocracy, nonocracy)

- World Order (states: international fragmentation, multipolarity, consolidated blocs, multilateral rules-based order, thick global governance)

- Inequality (states: various combinations of low/high international and domestic inequality)

- Conflict & Security (states: low violence, widespread non-state violence, civil/proxy war, international war, great power war)

Material subsystems (6):

- Energy (states: fossil-fuel dependence, peak oil and gas, green-tech breakthrough, low-carbon energy contraction)

- Climate (states: increased global heating of <2.5°C in 2100, 2.5-4°C, >4°C)

- Health (states: high/medium/low burden of disease)

- Food (states: status-quo global industrial production, agri-tech breakthrough, agro-ecological production, variable regional production, failed global industrial production)

- Transportation (states: fit for the future, fit for now, fragmented and failing)

- Information technology (states: limited rollout, managed rollout, unmanaged rollout)

The Method: Cross Impact Balance Analysis

Cross Impact Balance (CIB) analysis was developed by Wolfgang Weimer-Jehle in a 2006 paper. This method is particularly powerful for social systems because it can integrate different types of data and expert judgment about fuzzy relationships.

The core of the approach involves creating a judgment matrix showing all descriptors (ie all global subsystems and their possible states) and their relationships to each other, including:

- Whether relationships are promoting or inhibiting

- The strength and confidence level of each relationship

A crucial methodological constraint disciplines the analysis: scores within each judgment group must sum to zero. This “balancing constraint” prevents arbitrary or unconstrained assessments and forces careful consideration of trade-offs.

The model required 110 separate judgment sections (eg, “effect of world order on economy”), resulting in approximately 1,800 individual expert judgments (across the 45 different states). These judgments are supported by 200 pages of research and rationale, allowing independent assessment of their validity. The judgment model and it’s calculation matrix, are completely transparent.

The Mathematical Core: Finding Consistency

With 45 possible states across 11 descriptors, the model theoretically encompasses 4,050,000 possible scenarios or “futures.”

The CIB mathematical framework determines which scenarios are “consistent”, which means they are self-reinforcing. A consistent scenario is one where the various system states mutually support each other, creating a stable configuration.

Think of it like this: some combinations of system states reinforce each other (eg, strong democracy + multilateral cooperation + managed technology rollout), while others create contradictions that make them unstable (eg, authoritarian regimes + thick global governance).

The Findings: Three Attractors and a Narrow Path to Hope

The mathematics reveals that out of 4 million possible states, only 11 are fully consistent. These function as attractors in the 11-dimensional state space. Attractors are stable configurations toward which the global system naturally tends.

Three Major Attractors Emerge

Simplifying these results, Cascade Institute researchers identified three main types of attractors:

- The Illiberal Democracy Attractor: A world of democratic backsliding and constrained freedoms

- The Mad Max Attractor: Characterised by state failure, widespread violence, and collapsed governance, Homer-Dixon referenced Haiti as a current example

- The Hope Attractor: A positive future with improved human wellbeing

The relative size of these attractors matters enormously:

- Mad Max is big: Attracting approximately 500,000 of the 4 million scenarios, this represents the largest basin of attraction. It appears frighteningly easy for the global system to slide into this catastrophic state.

- Illiberal Democracy and Autocracy: Significant individual attractors exist in this space as well, though collectively they appear to absorb more scenarios than Mad Max.

- Hope is narrow: Drawing in only about 100,000 scenarios, Hope has the smallest basin of attraction among the major outcomes

However, there’s important nuance here. Later analytical runs showed that Hope is a “relatively deep attractor”, meaning that once in its basin, the world systems tend to stay there. It’s a harder equilibrium to reach but stable once achieved.

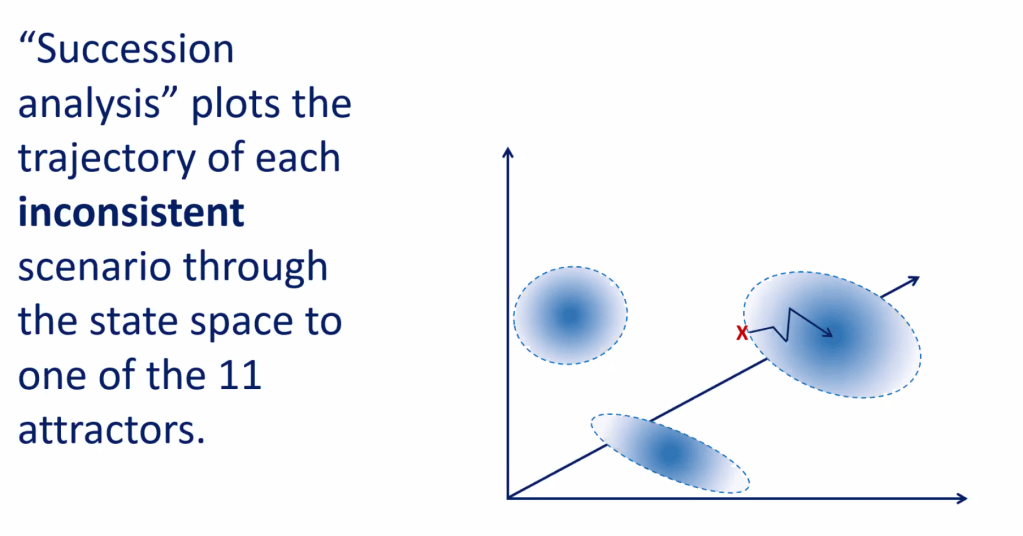

Succession Analysis

Further research by the CORE Model team will employ a method known as succession analysis (which tracks how inconsistent scenarios migrate through state space toward the consistent scenarios), to deduce the lowest barrier pathways through the model from the world’s present system states to the nearest edge of the hope attractor. This approach leverages the idea of a kind of reverse tipping point, high leverage policy/intervention points that could set off a cascade of transformation into the hope attractor, the system’s natural dynamics would pull us in.

The temporal aspects of the model are complex. Succession analysis functions as “an analogue of time” rather than explicit temporal modelling. The model is essentially “instantaneous” (showing stable states) rather than fully dynamic (showing detailed trajectories through time).

This is both a limitation and a practical necessity as fully modelling the temporal dynamics of 11 coupled systems risks being computationally intractable and would require even more uncertain judgments about rates of change.

The real value of this work emerges in its policy implications. The model isn’t just descriptive, rather it’s designed to identify intervention points.

Hope’s Limitations

However, even the Hope attractor isn’t utopian. As Homer-Dixon emphasised, “Hope is still Hot”, by which he meant that even this positive scenario involves significant climate heating and its associated challenges. The model doesn’t promise a return to pre-industrial conditions or easy solutions, just significantly better outcomes than the alternatives.

Critical Policy Target: Democracy

The analysis has already revealed very clear policy targets. Most notably, according to Homer-Dixon, maintaining democracy appears essential, as without democratic governance, “there appears no way there”, ie, no viable pathway to the Hope attractor emerges in the model.

This finding aligns with the Cascade Institute’s broader work on global systemic stresses, which identifies ideological fragmentation, polarisation, and political-institutional decay as critical stressors undermining humanity’s capacity to respond to other challenges.

Methodological Considerations and Ongoing Work

Homer-Dixon was refreshingly candid about the model’s current status and limitations. He acknowledged the model is “somewhat crude” but argued it provides a foundation for mapping paths toward transformation. This honesty is important, the model isn’t claiming perfect foresight but offering structured insight into complex dynamics. Furthermore, it is fully transparent, so users could adjust the settings according to new evidence. The CORE Model lends itself to modelling interventions that change the present state of world subsystems and deducing likely future states.

Sensitivity Analysis and Refinement

The research team is conducting extensive sensitivity analysis and converging on the “right” approach through iterative refinement. The rules used for succession analysis, Homer-Dixon noted, are “very important and make a difference to outcomes.”

This ongoing refinement is crucial. Early versions of complex models often reveal more about the modellers’ assumptions than about reality. But through systematic testing and adjustment, such models can become increasingly useful.

The forthcoming release of 200 pages of research and rationale supporting the 1,800 expert judgments will provide important grounding. This documentation will allow others to assess the judgments’ correctness and validity.

Next Steps and Using This Work

Homer-Dixon indicated the work is being prepared for publication in Nature, suggesting it will soon face rigorous peer review. He also noted that slide decks, mathematical details, and video recordings will be made available through ASRA’s YouTube channel.

We note that for researchers, policymakers, and organisations working on global catastrophic risk, several opportunities emerge:

For Researchers

- Examine the detailed methodology when published

- Apply similar CIB approaches to regional or sectoral polycrises

- Contribute to refining the expert judgments as new evidence emerges

- Extend the model to explore specific intervention scenarios

For Policymakers

- Use the framework to identify high-leverage intervention points

- Prioritise policies that maintain democracy and international cooperation

- Assess whether current policies push toward Hope or away from it

- Design policies with an understanding of system-level interactions

For Organisations

- Apply polycrisis thinking to strategic planning

- Identify how organisational actions contribute to global system stresses or resilience

- Engage with the Cascade Institute’s broader work on global systemic stresses

Finally, such approaches and tools are exactly the kind of frameworks that we have previously argued are missing from a lot of national risk assessment, so there is much potential to incorporate these methods when addressing global catastrophic risk, see our call for more focus on these issues in our recent peer-reviewed paper on New Zealand’s long-term resilience to global risks.

Conclusion

What makes the Polycrisis Core Model significant isn’t that it predicts the future because it doesn’t and it can’t. What it does is transform our understanding of possibility space.

Before this work, discussions about achieving positive global transformation were largely speculative. We could point to things that needed to change such as carbon emissions, inequality, authoritarian governance, but we lacked a systematic understanding of how these elements interact and which changes might trigger virtuous rather than vicious cycles.

Now, based on the CORE Model’s 1,800 expert judgments and rigorous mathematical analysis, we have something more concrete. The model demonstrates that Hope is possible but narrow, that certain policy targets (especially democracy) appear non-negotiable, and that we need to find ways to push the global system toward that Hope attractor’s basin.

The work is also a further wake up call. Mad Max attracts far more scenarios than Hope. Our default trajectory, absent deliberate intervention, trends toward collapse not transformation. This is something we have also detailed when describing the ‘hard landing ahead’ in previous blogs. This likelihood also means that investment in resilience (to Mad Max) remains a critical hedge for decision-makers (for examples of resilience options see our previous “NZCat” work).

But unlike in previous work, and thanks to the Cascade Institute’s work, we now have tools to map this terrain. We can identify leverage points, evaluate interventions, and design policies with an understanding of system-level consequences. The question isn’t whether transformation is possible, the model shows it is. The question is whether we’ll implement the changes necessary to reach it.

As Ben Okri challenged myself and other attendees at the recent ASRA Symposium: “We have to find better alternatives to the current direction of history.” The Polycrisis Core Model provides not just warning but a roadmap for doing exactly that.

Whether we follow it remains to be seen.

Further Resources:

- Cascade Institute: https://cascadeinstitute.org/

- ASRA (Accelerator for System Risk Assessment): https://www.asranetwork.org/

- Lawrence et al. (2024). “Global polycrisis: the causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement.” Global Sustainability

The webinar recording and slide deck are available on ASRA’s YouTube channel.