Matt Boyd & Nick Wilson

TLDR/Summary

- The US Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act (2022) mandated assessment of six major threats that could significantly harm human civilisation: pandemics, climate change, nuclear war, asteroid/comet impacts, supervolcano eruptions, and artificial intelligence (AI).

- RAND has produced a report representing the first comprehensive US government-mandated assessment of these risks.

- Key findings reveal that while asteroid impacts and supervolcanoes are better understood scientifically, the most pressing concerns come from human-influenced risks.

- The report identifies the threats with increasing likelihood of occurrence as pandemics, climate change, nuclear war, and AI, with pandemic likelihood projected to double or quadruple by 2100.

- Importantly, these risks are interconnected and can amplify each other – for instance, AI could exacerbate nuclear or pandemic risks.

- The report’s significance extends beyond mere assessment: it provides a foundation for the development of concrete central government response strategies and testing these plans through exercises, as mandated by the Act.

- This practical approach, combined with calls for international cooperation and expanded research, marks a crucial shift from theoretical discussion to actionable policy on catastrophic risks.

- While the report has some inconsistencies, its existence signals growing recognition that global catastrophic risks require coordinated global action.

- As these threats continue to evolve and interact, the findings provide a foundation for international collaboration on risk management – making this work relevant not just for the US, but for all nations concerned with humanity’s future resilience.

The US Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act

Enabled by the US Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act (2022) (US GCRMA), the Secretary of Homeland Security and the administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency directed RAND to produce a report on six threats and hazards considered global catastrophic risks (GCRs). The report assesses pandemics, climate change, nuclear war, asteroid/comet impacts, supervolcano eruptions, and AI.

The Act defines GCRs as ‘events or incidents consequential enough to significantly harm or set back human civilisation at the global scale’.

The Act also requires that subsequent work ensures each Federal Interagency Operational Plan be supplemented with a strategy to ensure the health, safety, and general welfare of the civilian population affected by catastrophic incidents, as well as ensuring that the strategies developed are validated through exercises.

RAND’s assessment of GCRs

RAND’s Global Catastrophic Risk Assessment analyses both natural hazards and human-created inventions and actions that could cause global catastrophe.

The report foreshadows its focus on processes and consequences (rather than a probabilistic risk assessment). Early chapters note the value of identifying causal chains to catastrophe and where these are more and less understood.

Each risk is described in terms of the likelihood of potential consequences across the categories of death, ecosystem instability, societal instability, and reduced human capabilities.

Supervolcanoes

The RAND Corporation’s report highlights the severe threat posed by supervolcanoes, which erupt approximately every 15,000 years. These events produce violent eruptions causing extensive damage through pyroclastic flows, ash clouds, and climate impacts that can span regional to global scales. The report emphasises that sulphur-containing gases entering the stratosphere could alter Earth’s climate for years, potentially threatening agriculture and billions of lives. While acknowledging these risks, RAND suggests the long-term atmospheric and climatic effects remain uncertain due to limited peer-reviewed evidence.

However, this assessment appears to underestimate the volcanic threat. While RAND focuses on supervolcanoes (Volcanic Explosivity Index [VEI] of 8+), smaller but still massive VEI 7+ eruptions, like Tambora in 1815, occur far more frequently—approximately every 625 years (see our study of the impact of Tambora). Even moderate eruptions (VEI 3-6) near major trade routes could trigger global catastrophes, if occurring at critical communication and trade hubs as documented in Nature.

This blog’s first author (MB) consulted with volcanology experts at Oxford and Cambridge Universities who revealed more extensive peer-reviewed evidence than RAND presents, particularly regarding climate and food supply impacts. The report’s projection of 1-2°C global temperature decreases over 1-2 years underplays literature showing 2-4°C drops lasting 10-20 years. RAND also appears inconsistent in emphasising massive potential casualties while downplaying climate effects.

Despite these limitations, the core message stands: even moderate volcanic eruptions could severely disrupt global society, with larger events threatening food security worldwide.

Asteroid/comet impact

Large asteroids are known as ‘world killers’ and the effects of an asteroid or comet just 300m across hitting the Earth would be felt worldwide. Impacts leading to country-sized devastation occur approximately every 100,000 years, and impactors large enough to cause global devastation strike the Earth every 10 million years.

RAND reports that work by the global planetary defence community has substantially increased our knowledge of asteroid risks, including efforts to detect existing asteroids (such as NASAs Near Earth Object Programme and Planetary Defense Coordination Office). The successful NASA DART mission tested and proved one method for deflecting objects in space.

Thankfully the infrequency of large impacts coupled with our emerging understanding of how to mitigate the risk, makes the risk of global catastrophe posed by asteroid or comet strikes very low, indeed probably the lowest of the risks identified in the RAND report.

Severe pandemics

RAND’s analysis warns that severe pandemics can inflict massive casualties and social disruption in remarkably short periods. The report highlights how human activities are amplifying pandemic risks, projecting a two to four-fold increase through 2100. While natural pandemics are becoming more frequent, the report also acknowledges the less quantifiable risks of laboratory accidents and engineered pathogens—noting historical incidents of accidental exposure and mishandled pathogens during biological research.

The report emphasises that technological advancement and improved pandemic preparedness could both reduce outbreak likelihood and minimise their impact.

However, newer research paints an even clearer picture of future risks. A 2023 study from the Center for Global Development projected Covid-19-scale pandemics every 33-50 years, with catastrophic events killing 80 million people expected every 120 years.

Preliminary findings from our own work on pandemic mitigation indicates that we largely know how to manage pandemics, but the appropriate responses vary by context. Increasing the capabilities and capacities measured by the Global Health Security Index appears to correlate with improved pandemic outcomes (in terms of excess mortality during the Covid-19 pandemic) for countries that are not islands. For island jurisdictions, tight border management appears effective, to buy time until a vaccine is available or other protections put in place.

It will be worth watching what advice emerges from the US with respect to global pandemic catastrophe, as each jurisdiction will probably need tailored advice.

Nuclear war

RAND finds that nuclear war could kill hundreds of millions of people directly and potentially billions of people indirectly through the effects of radiation, and the climate impacts of nuclear winter and famine. The indirect effects of nuclear war are less predictable than the direct impact of detonations and experts disagree on some key assumptions.

Nuclear war could wreak havoc with ecosystems, destroy government infrastructure, economies, and the function of national governments. Damages could total hundreds of trillions of dollars. Our own estimation of the impact on the small non-combatant nation of New Zealand exceeded NZ$1 trillion.

Depending as it does on human decision makers, the true probability of nuclear war is not knowable.

Regardless, RAND notes that deeply uncertain processes can have significant policy implications. The report evaluated the quality of evidence supporting estimations of the scale and severity of nuclear war impacts as below that of asteroids, pandemics, and supervolcanoes. Further research is urgently needed.

It is perhaps timely then that the United Nations (UN) delegations of Ireland and New Zealand recently introduced a resolution on the scientific study of the impacts of nuclear war. The UN First Committee on Disarmament approved the resolution on 1 Nov 2024, by a vote of 144 to 3, with 30 abstentions. If passed in December at the General Assembly, then the resolution mandates a 21-member international scientific panel to evaluate the immediate and downstream effects of nuclear war. This will be the first time the UN has done so since the 1980s.

Rapid and severe climate change

RAND states that human-induced climate change has the potential to disrupt the natural environment and ecosystems in ways that threaten the stability of society and human health and welfare. The effects of climate change will likely lead to death, disruption, and degradation of ecosystem stability, as well as slowing economic growth, and reduction of human capabilities.

The report cites UN Environment Programme probabilities across a range of global mean temperature thresholds, finding that 2-3°C rise by 2100 is most likely. However, a 1% chance of >4°C would bring catastrophic consequences.

The RAND analysis considers weak economic growth of <1% per annum for the remainder of the 21st century, a large social cost of climate change, and negative effects on poverty, consumption, and quality of life. GDP per capita could be lower than it is today, with effects worse in vulnerable countries and risks of state fragility.

Decades of scientific study mean that RAND has comparatively high confidence in their assessment of the risk of global catastrophe due to human-induced climate change.

Artificial intelligence

The RAND report acknowledges that emerging AI technologies could amplify existing risks from nuclear war, pandemics and climate change. Also, that AI systems have the potential to destabilise social, governance, critical infrastructure and economic systems. Malicious actors could employ AI, or AI systems underpinning critical systems could fail.

However, the likelihood of global catastrophe mediated by AI is highly uncertain and little empirical evidence exists for assessing either likelihood or consequences. As such the risk of AI is rated the most uncertain among the hazards examined in the report.

AI has no inherent ‘kinetic or physical effect’ and as such an AI catastrophe will manifest via some other catastrophe, affecting social, governance, economic, environment, and critical infrastructure systems, perhaps disempowering humans in decision-making.

Overall risk assessment

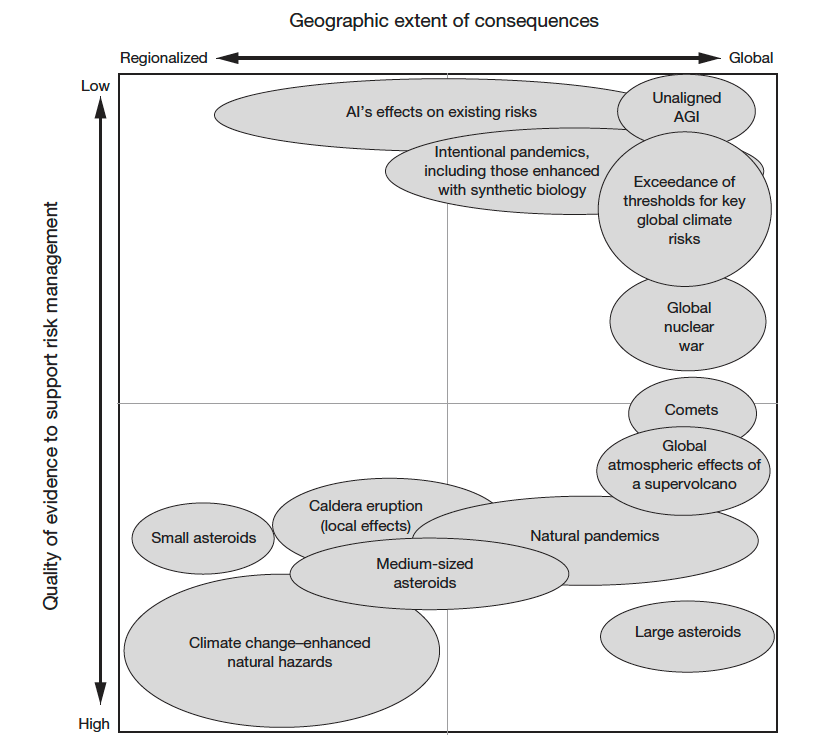

RAND presents their overall risk assessment in terms of the geographic extent of the global catastrophes assessed, and the quality of evidence that can support risk management, see the Figure below.

From the Figure we see that large asteroids, natural pandemics, and supervolcano eruptions have the potential to adversely impact the entire globe, and therefore every human on Earth. Quality evidence exists to guide management of these risks, but global cooperation is needed.

Global nuclear war, extreme climate change, and AI also have the potential to cause global catastrophe, but more evidence is needed to understand how to best mitigate these risks. There is also inherent uncertainty due to lack of any precedent.

RAND assesses that the risks associated with AI, climate change, nuclear war, and pandemics are increasing.

Additionally, the risks are interconnected, and all are influenced by the rate of technological change, the maturity of global governance and coordination, the failure to advance human development, and interactions among these hazards.

The report states that we can take technical and logistical action to mitigate risks where good evidence exists to guide action.

We can improve governance of risks where human behaviour amplifies the risk.

We can learn about risks for which there is yet insufficient evidence to recommend action.

RAND notes the need for enhanced institutions at all levels of governance (including internationally) able to implement these responses and risk management approaches.

Additionally, the report recommends a portfolio approach across these risks, collective action at all levels, the need to address deep uncertainty with scenarios and stress tests of the risk management portfolio, and working across diverse values, objectives and expectations.

Report recommendations

- Incorporate comprehensive risk assessments into management of global catastrophic and existential risks

- Develop a coordinated and expanded central government funded research agenda to reduce uncertainty about global catastrophic and existential risks and to improve the capability to manage such risks (analogous to a recommendation by NZ’s former Productivity Commission)

- Develop plans and strategies when global catastrophic and existential risk assessments are supported with adequate evidence.

- Expand international dialogue and collaboration that addresses global catastrophic and existential risks

- Adapt planning and strategy development to address irresolvable uncertainties about global catastrophic and existential risks.

Commentary

The RAND report is to be lauded. Although it has its weaknesses and inconsistencies. For example, having rejected the primacy of probabilities in assessing many of these global catastrophic risks, detailed probabilities are presented throughout some of the chapters. Having questioned long-term utilitarian arguments for action to prevent catastrophic and existential risks in early chapters, the report then employs them in the pandemic chapter (p.72). For several hazards the risk of severe climate impacts and the failure of global agriculture is noted (eg, nuclear war/winter, supervolcanoes, asteroid impact), yet resilience measures such as ‘stockpile food and medicine’ form the basis of the sketch of mitigation measures, rather than gesturing to a diverse and resilient global food supply and food system.

It also appears some offers by leading experts to contribute peer review of the report were not taken up. This runs against our previous arguments that national risk assessments must engage a wide body of experts and the public iteratively. Such review is critical when chapters are being written by two, or even just one contributor.

However, this RAND report is just the first step mandated by the US GCRMA. When one of us (MB) wrote about the Act back in Feb 2023, it was noted that the Act requires the assessment of these risks (the current RAND report), but then subsequently:

- A report on the adequacy of continuity of operations and continuity of government plans based on the assessed global catastrophic and existential risk.

- An Annex in each Federal Interagency Operational Plan containing a strategy to ensure the health, safety, and general welfare of the civilian population affected by catastrophic incidents.

- An exercise as part of the national exercise program, to test and enhance the operationalization of the strategy.

We must now await these developments in the US. But given the clear need for global coordination on these risks, other countries (including NZ) should use the RAND report to inform their own ‘interagency operational plans’ to ensure health, safety, and general welfare in the event of any, or any combination or, these six hazards, along with other potentially catastrophic scenarios such as massive solar storms or cyber-attacks.

Ongoing technological development should prioritise technologies that tend to reduce global catastrophic risk, rather than those that amplify it.

Coordinated governance of these risks should be developed in the form of agreements, treaties, collaborative knowledge seeking exercises, and investment. (See our recent arguments for such pandemic cooperation between Australia and NZ).

This action needs to start now, because there is a growing risk that these potential catastrophic processes will undermine our ability to mitigate and respond to them.

The UN has started to take global catastrophic risks seriously. Mention of these issues at the beginning of the 2024 Pact for the Future, also the abovementioned Ireland/New Zealand sponsored UN resolution are to be commended. But other risks need more work. A global pandemic treaty met serious hurdles of national and regional self-interest, and there is no collaborative global body directed against the risk of global catastrophe due to volcanoes. The world needs to lift its game, and hopefully this RAND report is a timely reminder that nations need to make wise choices now, that ensure affordances when they need to act later in the face of potential catastrophe.