TLDR/Summary

- Early COVID-19 analyses suggested countries with higher Global Health Security (GHS) Index scores had worse mortality, contradicting pre-pandemic validation. Our new research with improved methodology resolves this paradox.

- We analysed 47 islands and 142 non-islands separately, finding higher GHS Index scores strongly predicted lower excess mortality for non-islands only (models explained 48% of variance), while islands showed no relationship.

- Island jurisdictions experienced much lower excess mortality overall (59 vs 193 per 100,000 population across 2020–21) because border controls and geographic isolation were more protective than the internal health capacities the GHS Index measures.

- We addressed earlier methodological flaws by analysing islands separately, using cumulative age-standardised excess mortality data (2020-2021), pre-pandemic GHS scores (2019), appropriate statistical transformations, and controlling for GDP and corruption.

- The “Risk Environment” category (including socioeconomic, political, and governance factors) was particularly predictive of outcomes and is uniquely assessed by the GHS Index compared to other preparedness tools.

- Our findings validate the GHS Index as a pandemic outcome predictor for non-island jurisdictions but highlight that border biosecurity and broader societal factors (democracy, inequality, governance) deserve greater emphasis in pandemic preparedness planning.

Controversy over the Global Health Security Index

The Covid-19 pandemic caught much of the world off guard, raising crucial questions about how well existing metrics of pandemic preparedness, such as the Global Health Security (GHS) Index, predict real-world outcomes.

The Index was designed in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic, to benchmark countries’ abilities to prevent, detect, and respond to biological threats. But, early analyses during the Covid-19 pandemic suggested a paradoxical pattern: countries with higher GHS Index scores seemed to experience worse mortality outcomes, not better ones.

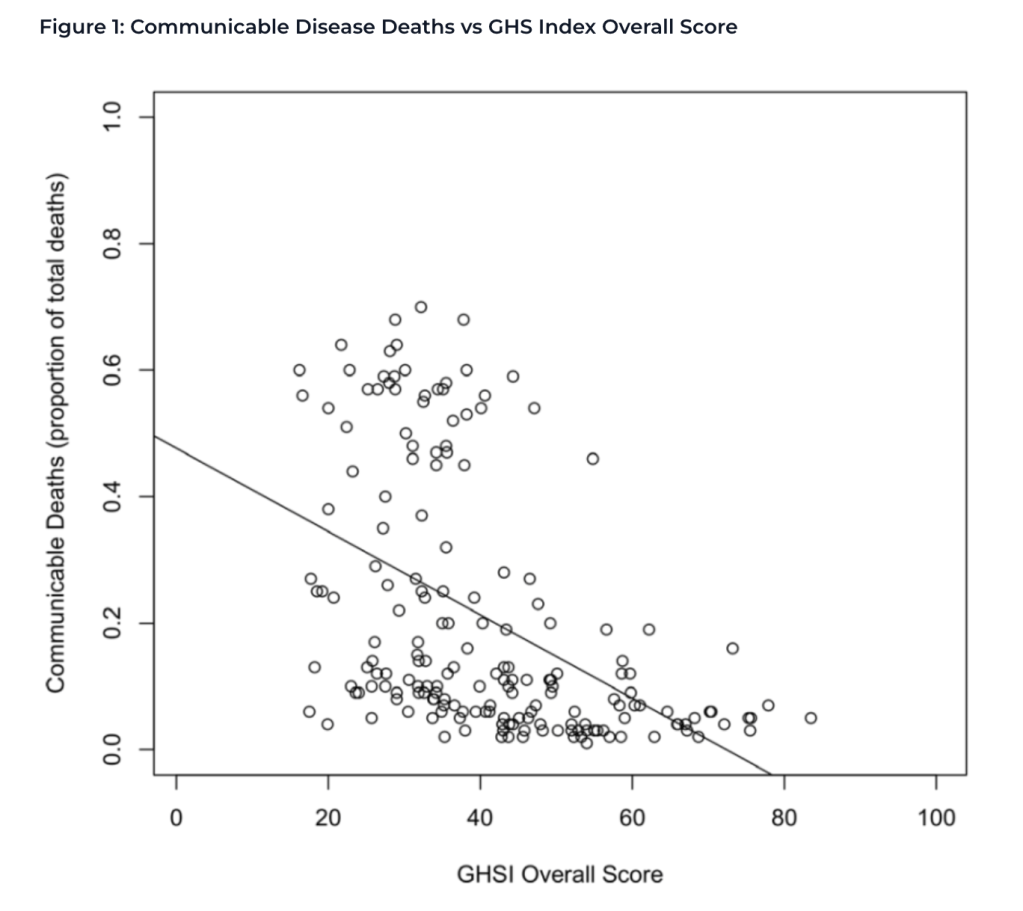

This finding was unexpected, especially because our own prior research established links between higher GHS Index scores and fewer deaths from a range of communicable diseases. This validation analysis using pre-pandemic data showed that for each 10-point increase in GHS Index score, there was a 4.8% decrease in the proportion of national deaths attributable to communicable diseases (see Figure below).

Figure 1: Communicable Disease Deaths vs GHS Index Overall Score

Therefore, in the Covid-19 pandemic, how could countries deemed “most prepared” suffer the most? Was the GHS Index somehow flawed as a predictive tool for pandemic outcomes? Several factors might explain the early paradoxical findings:

- Countries with better surveillance systems (generally those with higher GHS Index scores) likely detected and reported mortality more accurately

- Data early in the pandemic didn’t account for differences in population age structures

- Analyses often used just the reported Covid-19 deaths rather than more accurate estimates of cumulative excess mortality through the pandemic

- The timing of analyses (early pandemic vs later stages) could affect results

Problems with Early Analyses

Early analyses faced problems with data quality and timing. Additionally, early studies didn’t properly account for the fact that some jurisdictions, such as island nations, exhibited different pandemic management strategies and had different pandemic experiences.

Many islands deployed protracted border closures, or stringent border biosecurity restrictions, keeping cases low despite poor internal health security capacities in some cases.

Addressing Methodological Weaknesses

In our recently published study in BMJ Open, we sought to address the methodological critiques of earlier work and provide a more definitive analysis of the relationship between GHS Index scores and Covid-19 outcomes. Our approach included several key improvements:

- Separating islands and non-islands: We analysed 47 island and 142 non-island jurisdictions separately, recognising their fundamentally different geographic situations and pandemic response options. We defined island jurisdictions as those surrounded by water, while ignoring structural connections to other land masses (including places like Singapore and the UK as islands).

- Using age-standardised excess mortality: Rather than relying on reported Covid-19 deaths, we used age-standardised excess mortality for 2020-2021, which accounts for both undercounting and differences in population age structures between countries. There are several potential problems when using this kind of data, however the Global Burden of Disease Study Demographic Collaborators sought to overcome these by establishing cumulative excess mortality estimates based on six weighted baseline models, across 10 years’ of pre-pandemic data. This approach should lessen the effect of outliers and trends extrapolated from few datapoints.

- Appropriate statistical transformations: We transformed right-skewed data (GDP and excess mortality) using logarithmic and cube root transformations respectively, making them more suitable for statistical analysis.

- Using pre-pandemic GHS Index scores: We used 2019 GHS Index scores (not influenced by pandemic outcomes) rather than 2021 scores that were updated after the pandemic began.

- Controlling for key variables: We controlled for GDP per capita (adjusted for purchasing power parity) and government corruption in our analyses.

Key Findings: Islands and Non-islands Differed Dramatically

Our new research reveals a striking difference between island and non-island jurisdictions:

For non-island jurisdictions:

- Higher GHS Index scores strongly predicted lower age-standardised excess mortality during 2020–2021, even after controlling for GDP and government corruption

- The association was statistically significant and robust

- The model explained 48% of the variance in excess mortality across 128 non-island jurisdictions

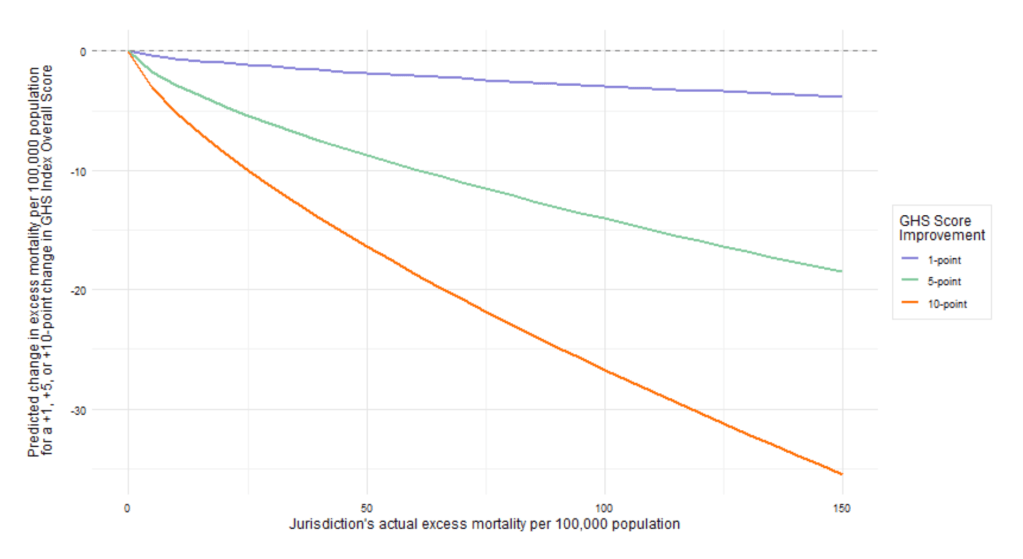

- Based on our modelling, a hypothetical jurisdiction with an excess mortality of 100 per 100,000 population, could expect to have a reduction of 26.7 deaths per 100,000 population if their GHS index score was 10 points higher.

For island jurisdictions:

- No meaningful relationship between GHS Index scores and excess mortality was found

- Island jurisdictions generally experienced much lower excess mortality regardless of GHS Index score (mean 59 vs 193 per 100,000 for non-islands)

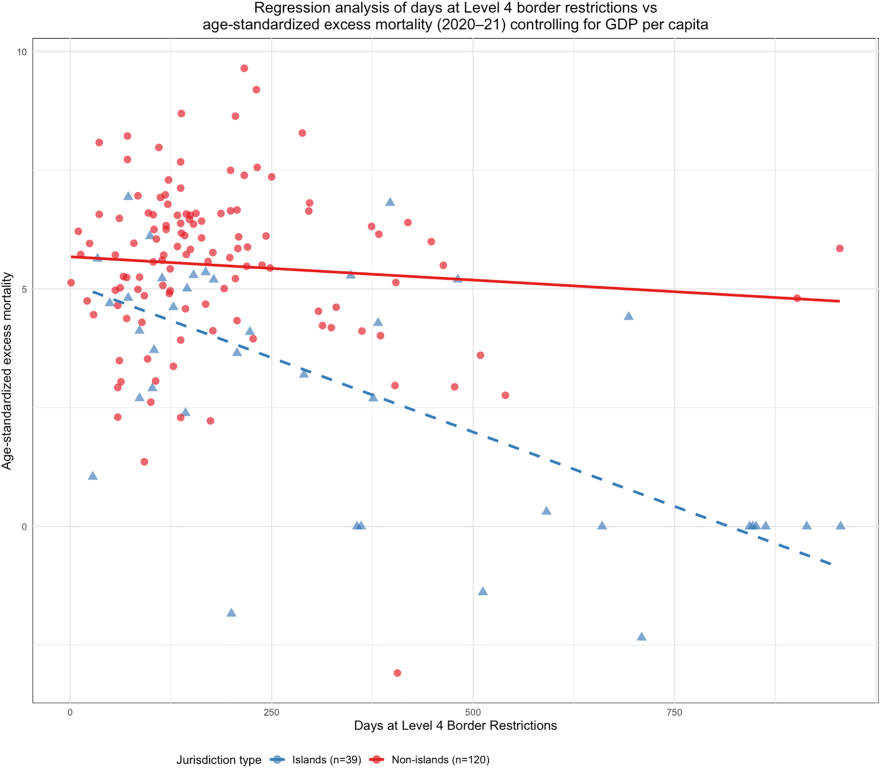

The figure below shows the relationship between GHS Index scores and predicted change in age-standardised cumulative excess mortality for non-islands.

Figure 2. Predicted relationship between age-standardised cumulative excess mortality 2020-2021 and GHS Index score for changes of +1, +5, and +10 GHS Index points, for non-island jurisdictions

This pattern suggests that geographic isolation, which made effective border controls possible, was more important for islands than the internal capacities measured by the GHS Index, which predicted pandemic mortality in non-islands.

Category-level Insights

When we analysed the six GHS Index categories separately for non-islands, we found that all categories except “Compliance with International Norms” were associated with lower excess mortality.

The strength of the “Risk Environment” category is particularly noteworthy. This category includes assessment of socioeconomic, political, and governance factors that affect vulnerability to outbreaks, including government effectiveness, public confidence in governance, and levels of inequality. Interestingly, this category is not included in other preparedness assessment tools like the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation. This is noteworthy, as additional work we’re conducting indicates that higher income inequality predicted worse health outcomes early in the pandemic, and that more democratic island jurisdictions had better health outcomes.

Economic Performance Findings

We also examined economic performance during the pandemic. However, model fit was poor, suggesting that factors beyond health security capabilities drove economic outcomes (our ongoing work points to income inequality as one predictor of worse macroeconomic outcomes early in the pandemic).

Conclusions

Our research supports the validity of the GHS Index as a predictor of pandemic outcomes for non-island jurisdictions. It also further highlights the stark differences between islands and non-islands during the Covid-19 pandemic. These findings suggest border biosecurity deserves greater focus in pandemic preparedness metrics and in the actions taken by countries to protect their populations from large scale biological threats.

This finding is consistent with other recent analyses showing a strong relationship between taking an explicit exclusion/elimination strategy against Covid-19 and a country experiencing low excess mortality during 2020-21. A similar protective relationship was found for high income OECD island states, which took an exclusion/elimination strategy.

The strong association between the “Risk Environment” category and pandemic outcomes underscores the importance of broader societal factors beyond traditional health system capabilities, including increasing democracy and reducing inequality and government corruption.

With appropriate methodological approaches, the GHS Index does predict pandemic outcomes, but not uniformly across all types of jurisdictions. This nuanced understanding can guide effective pandemic preparedness efforts in the future, as we continue to face biological threats ranging from emerging infectious diseases to deliberate biological attacks.