A Tale of Two Conferences Part II: ASRA ‘Currents of Change’ Symposium 2025

(In-depth read, 15 min)

TLDR/Summary

- Part II of a two-part blog series reporting on a pair of crisis/disaster risk conferences – this one covers the ASRA ‘Currents of Change’ Symposium, which offered a refreshing contrast to the UN’s symptom-focused approach detailed in Part I.

- ASRA brought systems thinking to crisis management – 250 multidisciplinary experts tackled interconnected “polycrisis” issues rather than isolated disasters, focusing on the deeper stresses that drive cascading failures.

- Keynote speakers delivered transformation-focused messages – Poet Ben Okri challenged humanity to become “the people our times require,” while Christiana Figueres emphasised that “linear thinking has no place” in addressing systemic risk.

- Practical tools emerged alongside theory – ASRA launched STEER, a beta tool for systemic risk assessment, and workshops demonstrated hands-on polycrisis analysis and intervention design using real global stresses and future scenarios.

- The hard truth: single solutions won’t work – Whether it’s capitalism, carbon emissions, or specific leaders, there’s no single root cause to our interconnected crises; siloed institutions impede the interdisciplinary approaches we desperately need.

- Bottom line: humanity has the frameworks and community, but the race against time continues – ASRA provided genuine hope and practical starting points, but whether this scales fast enough to prevent humanity’s “hard landing” remains the crucial question.

Definitions

Global systemic stresses: long-term processes that weaken the resilience of critical global systems by increasing pressures, sharpening contradictions, and expanding vulnerabilities. These stresses make systems more vulnerable to trigger events that push them into a crisis.

Polycrisis: The simultaneous occurrence of multiple, interconnected crises that exacerbate each other, creating a situation more severe than the sum of its parts. It’s not just a collection of unrelated crises, but rather a situation where different crises interact and amplify the negative impacts of each other.

Systemic risk: The potential for multiple, increasingly severe, abrupt, differentiated yet interconnected, and potentially long-lasting and complex impacts on coupled natural and human systems. Systemic risk implies the potential for system-level breakdown and cascading consequences across human and natural systems.

Metacrisis: In this blog ‘metacrisis’ refers to the collection of forces: evolutionary, social, technological, and game theoretic, that drive and give rise to global systemic stresses, and resulting crises, polycrisis, and systemic risk.

Introduction & Context

Twenty-four hours after leaving the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Global Platform in Geneva, somewhat pessimistic about humanity’s trajectory, I found myself at Les Fontaines in Chantilly Gouvieaux, France, for an entirely different kind of gathering.

The Accelerator for Systemic Risk Assessment (ASRA) was hosting the ‘Currents of Change’ Symposium – the first transdisciplinary global meeting dedicated to action on systemic risk.

The Symposium offered what the UNDRR Global Platform appeared to miss: clear-eyed analysis of the deeper and interconnected stresses driving cascading crises, coupled with actionable frameworks for addressing them.

ASRA represents a fresh approach to global catastrophic risk. As a network of 90 transdisciplinary experts, it brought together 250 systemic risk practitioners and stakeholders to tackle what ASRA defines as systemic risk: “the potential for multiple, increasingly severe, abrupt, differentiated yet interconnected, and potentially long-lasting and complex impacts on coupled natural and human systems.”

Unlike traditional disaster risk conferences focusing on specific hazards, ASRA addressed the underlying patterns generating cascading failures across interconnected systems. The goal: prevent, mitigate, adapt, and transform away from systemic risk before it overwhelms humanity’s response capacity.

Opening Address: Ben Okri’s Call for Transformation

British/Nigerian poet and author Ben Okri gave the opening keynote, a moving, powerful account of humanity’s current predicament that immediately distinguished this gathering from conventional policy conferences. As a renowned novelist, Okri brought a different lens that cut through technocratic language to human realities.

“Many things have come into reality that cannot sustain themselves,” Okri observed – capturing what metacrisis theorist Daniel Schmachtenberger had described as humanity’s “self-terminating race” (see Part I).

But rather than dwelling in despair, Okri challenged humanity towards transformation thinking: “We must not make the mistake of thinking that the present will become the future.”

His diagnosis was unflinching. “Nations cannot talk of making themselves ‘great’ at the expense of making the rest of humanity small,” directly addressing the zero-sum thinking that underlies the competitive dynamics driving many global systemic stresses.

Most crucially: “We cannot combat the difficulty of our times as the people we used to be, we have to be fit and healthy, and we have to create wider and wider communities and alliances and we have to fight the evil of our times intelligently.”

This call for intelligent, collaborative action echoed throughout the Symposium’s technical sessions.

Keynote: Christiana Figueres on Transformative Change

The first keynote session saw Christiana Figueres, former Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and architect of the Paris Agreement, demonstrate how systemic thinking translates into concrete action. Her presentation exemplified the Symposium’s approach of inclusive systematic analysis with practical optimism.

“In the face of systemic risk, linear thinking has no place today,” Figueres began, directly addressing the siloed thinking that limited many of the UNDRR discussions I had attended the previous week (see Part I).

We have the technology and understand interconnectedness, she continued, the question is implementation. Furthermore, rather than aiming to minimise our impact, we should actively seek to restore nature, shifting from ‘sustaining’ to ‘regenerating.’

Costa Rica provided her key example, where laws now facilitate payment for environmental services, resulting in increased forest cover from 29% to 55%. This demonstrates how changing incentive structures drives systemic change.

Figueres used the metaphor of a spider web for interactions in complex systems, explaining that we can’t control the web through top-down decrees, but we can observe “which threads are being pulled and how” and identify effects and leverage points where small changes create large systemic shifts.

Most importantly, Figueres identified a crucial constraint: “The scarcest resources at the moment are kindness and love.” She warned against letting news feeds crowd out genuine learning sources, including learning from the natural world. In a similar vein, I’ve previously blogged on Jaron Lanier’s calls for deleting all your social media ‘right now’, in my post on Covid, Trump, and algorithms.

Panel Discussions: Scale, Speed, and Systemic Solutions

ASRA Symposium panels tackled how we can meet the scale, scope and speed required for transformation. Unlike conferences focusing on incremental improvements, panellists grappled directly with the need to change human systems.

Participants spoke of bold actions, trust, and “crazy imagination.” One participant noted that, “change happens at the speed of trust,” and “we need to be good ancestors, that’s all.”

But the panellists also honestly assessed barriers, noting for example that Ministers of Finance lack technical understanding of systemic risk. We need bold moves in building systemic resilience so that human systems can handle the stress of the transformation that is required to reduce risk in the long term. However, the current efficiency vs resilience trade-off balance is wrong – we’ve built fragile systems optimised for short-term performance. We must stress-test our systems (whether financial, trade, food, or whatever vital system) and ask if the future we’re creating is resilient to the shocks that are increasingly likely. These stress tests require facilitated dialogue and knowledge sharing across the sectors and systems.

On the required foresight, participants emphasized anticipatory governance as key. Long-term efficiency comes through resilience, not optimisation, because iterated disasters and shocks will undermine efficient systems more over time than resilient systems.

Unfortunately, current crisis response follows whack-a-mole patterns addressing symptoms not causes. Humanity lacks the appropriate anticipatory governance, mechanisms to effect system redesign, and cross-border, regional and global coordination. In particular, we need to stop trying to solve global problems with national tools (as this will lead us into the game theoretic traps and harmful zero-sum dynamics).

“We shouldn’t fix the past, we need to build the future. It was these old systems that have led us here,” noted one panellist. Furthermore, we should act with “good enough information and fast enough action” rather than delays in search of perfect knowledge and optimal decisions.

The way the world seems stuck in rigid historical frames and decision processes, maladaptive in a present world of crisis and existential threats, reminds me of a scene in the film No Country for Old Men. Once he has outwitted the hero, villain Anton Chigurh observes:

“If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?”

The world and its legacy rule-based institutions appear to be in a similar bind. A new system of rules and processes is needed, or humanity will be brought “to this”.

Launch of the STEER Tool: Practical Systemic Risk Assessment & Response

At the Symposium, ASRA launched STEER (Systemic Tool to Explore and Evaluate Risks), a tool designed to help users ‘steer’ away from systemic crisis and toward solutions.

Currently in beta, STEER will make systemic risk assessment accessible to organisations, governments, and researchers across all systems and sectors.

STEER represents practical systems thinking and helps users map interconnections (systemic risk assessment) and identify intervention points (systemic risk responses) for systemic impact, rather than analysing risks in isolation. A combination of drop down menus, tutorial material, and prompts for reflection and action guide users through the processes of systemic risk assessment and response.

STEER will be publicly launched later this year, but feedback from conference attendees (all experts on systemic risk) beta testing the platform was very positive.

The ASRA Symposium provided opportunities for attendees to engage in the kind of processes that STEER encourages, through various workshops and side-events. I managed to attend two of these.

Workshop 1: Understanding Systemic Risk as Polycrisis

I participated in a breakout session facilitated by the Cascade Institute. This provided a hands-on polycrisis analysis exercise. The workshop highlighted global stresses and groups plotted possible interactions among these along with the triggers that could tip such interactions into crises. This helps us understand why so much is going wrong at the same time.

The theoretical basis for the Cascade Institute’s approach is their stress-trigger-crisis model. The model shows that stresses push systems toward points where triggers might create disequilibrium (and likely associated harm in human and ecological systems). Even without triggers, inexorable stressors will push systems into potentially harmful new states (eg, as the left hand depression in the figure below becomes shallower). Averting crises requires acting on stresses of three types: pressures, contradictions, and vulnerabilities.

The Institute previously identified 14 global systemic stresses which create cascading failure conditions for humanity, and which must be addressed to have hope of mitigating the present polycrisis (you can read more about these here):

- Climate heating

- Ecological degradation

- Toxicity

- Zoonotic disease transfer

- Demographic divergence

- Concentrated industrial food production

- Changing energy supply

- Financial interconnectedness

- Economic headwinds

- Economic inequality

- Ideological fragmentation and polarization

- Political-institutional decay

- Great power hegemonic transition

- Propagation of artificial intelligence

Working groups mapped interactions between three assigned stressors each, analysing how crises emerge when triggers act within these interactions. Each crisis can become a trigger within other patterns.

For example, my group was tasked with considering interactions among:

- North-South demographic divergence

- The concentrated nature of industrial food production

- Rising economic inequality

Interactions between these factors could be stressed further by events such as a policy shift in migration settings, or synchronous heatwaves in critical food production regions, leading to a crisis of workforce availability and food production, resulting in famine or war, with these crises then being the triggers of other global crises in cascading fashion.

The exercise rapidly demonstrated how current conditions create multiple, interacting, cascading failures – a polycrisis rather than isolated events. And we only considered three of the 14 global stresses!

Crucially, we brainstormed interventions for crisis mitigation through anticipatory action, such as sensible migration policies, sustainability criteria on imports, more heterogeneous distributed food systems, with food system buffers, and policies that alleviate economic inequality to hedge against short-term price shocks.

Key insight: There’s no single root cause of a polycrisis. It is not simply capitalism, carbon emissions, or the actions of particular leaders, but everything in conjunction. Single-point solutions won’t work. Siloed institutions impede solutions, which require interdisciplinary complex systems thinking.

Workshop 2: Preparing for Catastrophic System Failure

Another workshop facilitated by David Korowicz addressed whether catastrophic system failure can be mitigated ahead of time. We contemplated a scenario where (for the purposes of the foresight exercise) a national Cabinet has knowledge that a catastrophe severely decreasing goods, services, and energy access will happen in either 1, 4, or 8 years. Our group was tasked with considering how we would act with such information under the 4-year time horizon.

Roughly the results of our deliberations can be summarised as follows:

- Prevent panic while being clear resilience is a fundamental priority and the nation needs to start seriously working to mitigate likely effects of future crises.

- Assess physical security and available resources, ensuring physical safety and liaising with trusted international partners.

- Strengthen connections at all levels across government and society (families, communities, regions, international).

- Analyse complex reactions to crisis – how will people and countries respond? Will there be national hoarding with export controls? Ensure appropriate engagement with behavioural scientists.

- Map consequences for energy, transport, food, and communications systems.

- Stocktake the minimum functions required to sustain society according to hierarchy of needs (water, food, shelter, energy, etc).

- Develop mitigation options for each critical function in context of the catastrophe.

- Ensure redundant structures for communications, food, shelter.

- Strategic stockpiling while understanding supply constraints from other jurisdictions doing the same.

- Roll out incentives for electrification, local biofuels, distributed food production, and other resilience measures.

- Sequence and prioritise all interventions for maximum effectiveness.

Admittedly all the above were developed on the fly in half an hour, but the exercise raised two key questions for me.

- First, this all sounded incredibly familiar, and is basically the content of our own organisation’s detailed report on New Zealand’s vulnerability and resilience options against the risk of Northern Hemisphere nuclear war.

Recent media reporting on our study can be found here. You can read the rich and detailed report here, which is effectively a maturity model for resilience to global catastrophic risks, including one-page ‘cheat sheets’ for each key sector and for global catastrophic risk management.

- Second, why haven’t governments of the world conducted this kind of exercise, and developed and implemented exactly these plans and programmes, in conjunction with their citizens, given the perilous state of the world?

The workshop discussions also highlighted that this kind of resilience doesn’t depend on nationalistic self-sufficiency but on creating systems that are less susceptible to cascading collapses: locally resilient food and energy, regional governance, delinking from fragile global finance, mutual support networks. But also, and importantly, linkages with regional partners, collaborations of nations to ensure trade and supply through investment in strategic infrastructure and plans, and the avoidance of hoarding, which although seems rational for individual jurisdictions, could actually lower the global mean ability to ride out the crisis, creating overall more harm.

Addressing the Causes of Global Systemic Stresses themselves

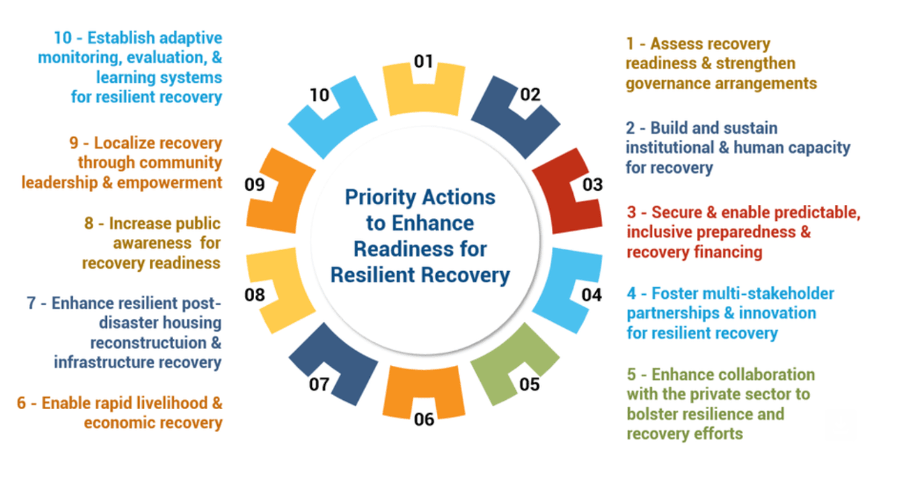

The workshops demonstrated that there are positive steps humanity can take towards limiting future catastrophe harm, even harm stemming from system-wide failures. We can implement systems thinking, map systemic interactions, develop resilience through anticipatory governance, conduct preparedness exercises, and reduce the human and environmental impact, and therefore depth of the economic harm that global systemic risk threatens.

ASRA’s greatest contribution was acknowledging this challenge while providing concrete intervention tools. Much more work is needed, particularly to address what drives these global stresses, including rivalrous dynamics preventing coordination, exponential technological advancement creating risks faster than assessment is possible, and resource degradation amid coordination failures. The impact of global stress reduction through systems thinking and action may still not be enough, because civilisation’s underlying dynamics don’t support such action. We’re potentially stuck in evolutionarily stable strategies where aggressive, exploitative behaviours outcompete cooperative, long-term alternatives – even when cooperation ensures collective survival.

All that said, the frameworks discussed and exercised at the ASRA Symposium offer genuine starting points for a new cognitive frame and for systemic intervention.

Conclusion: Building on Systemic Foundations

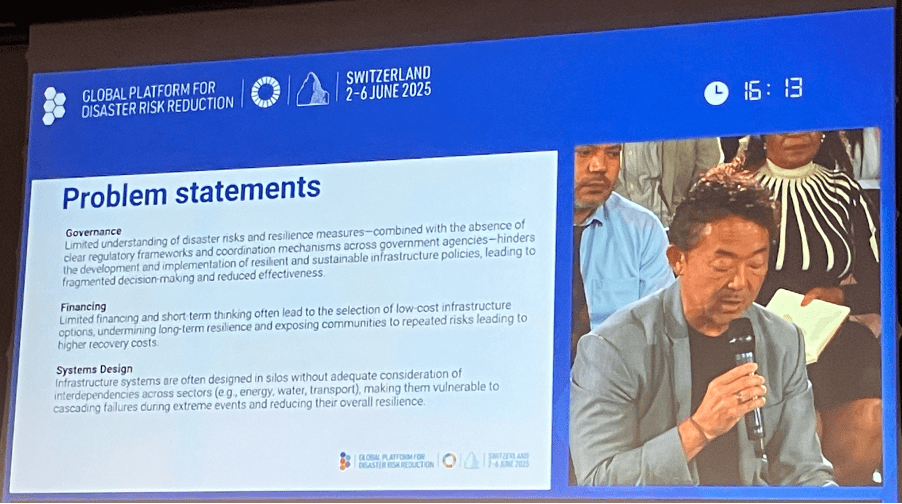

The contrast between the UNDRR Global Platform and the ASRA Symposium was striking and illuminates the limitations of current disaster risk reduction efforts, which are probably largely driven by historic silos.

While UNDRR demonstrated genuine commitment to developing resilience, discussion remained trapped within frameworks addressing symptoms rather than systems. ASRA took a fundamentally different approach, placing difficult systemic questions at the analytic heart. The result was honest assessment combined with practical intervention tools.

Most importantly, ASRA provided a transformation-focused community of practice. The Symposium demonstrated that systemic risk assessment isn’t an abstract academic exercise. It’s an urgent practical necessity for decision-makers navigating interconnected worlds where risks cascade faster than traditional approaches can address. This practical necessity needs to be resourced. Analysts and decision-makers across all vital sectors and systems need time and space to cooperate, coordinate, and hash-out these problems around the same table.

The challenge of disaster risk reduction, building immunity to global catastrophic risks, and transforming human systems away from those that generate these risks remains enormous. Changing competitive dynamics and evolutionarily stable strategies requires changes from individual consciousness right up to global governance.

We can respond and recover from various crises, we can build resilience and mitigate the impact of future crises, we can reduce systemic risk through judicious systems transformation, we can mitigate the polycrisis by minimising the global systemic stresses, but only by intervening on the forces comprising the metacrisis can we prevent global stresses and crises being thrown up again and again, in increasingly severe form.

I reported Daniel Schmachtenberger’s views in Part I. He notes that the race dynamics of humanity are self-terminating. Individual improvement is insufficient – we need to bend the entire arc of human history. Ben Okri echoed this at ASRA: “We have to find better alternatives to the current direction of history.”

But frameworks, tools, and community emerging from initiatives like ASRA provide hopeful foundations and Ben Okri’s challenge echoes as warning and invitation. We cannot combat our times’ difficulties as the people we used to be, but we can choose to become the people our times require.

Whether this mindset and process scales and accelerates quickly enough to bend the arc of human history before the “hard landing” becomes inevitable remains the question.